In 2014, five years into his NFL career, defensive lineman Michael Bennett became a Super Bowl XLVIII champion playing for the Seattle Seahawks. For most athletes, such an accomplishment is already a remarkable professional legacy. But Bennett’s on-field aptitude (he’s also a three-time Pro Bowler) stands secondary to his ongoing humanitarian work and social justice activism. In 2015, he used a press conference to speak out against a teammate’s criticism of the Black Lives Matter movement.

The following year, he joined fellow NFL player Colin Kaepernick by refusing to stand during “The Star-Spangled Banner” — a form of protest against police brutality and systemic racism that Bennett (then playing for the Philadelphia Eagles) continued after Kaepernick left the league. (Pushback led to a viral fake photo of Bennett burning the American flag.) In both his memoir — Things That Make White People Uncomfortable, published in 2018 — and the podcast Mouthpeace, which he hosts alongside his wife, artist Pele Bennett, he has tackled everything from concussions to over-policing. The couple also leads a food justice foundation dedicated to promoting nutrition in underserved communities.

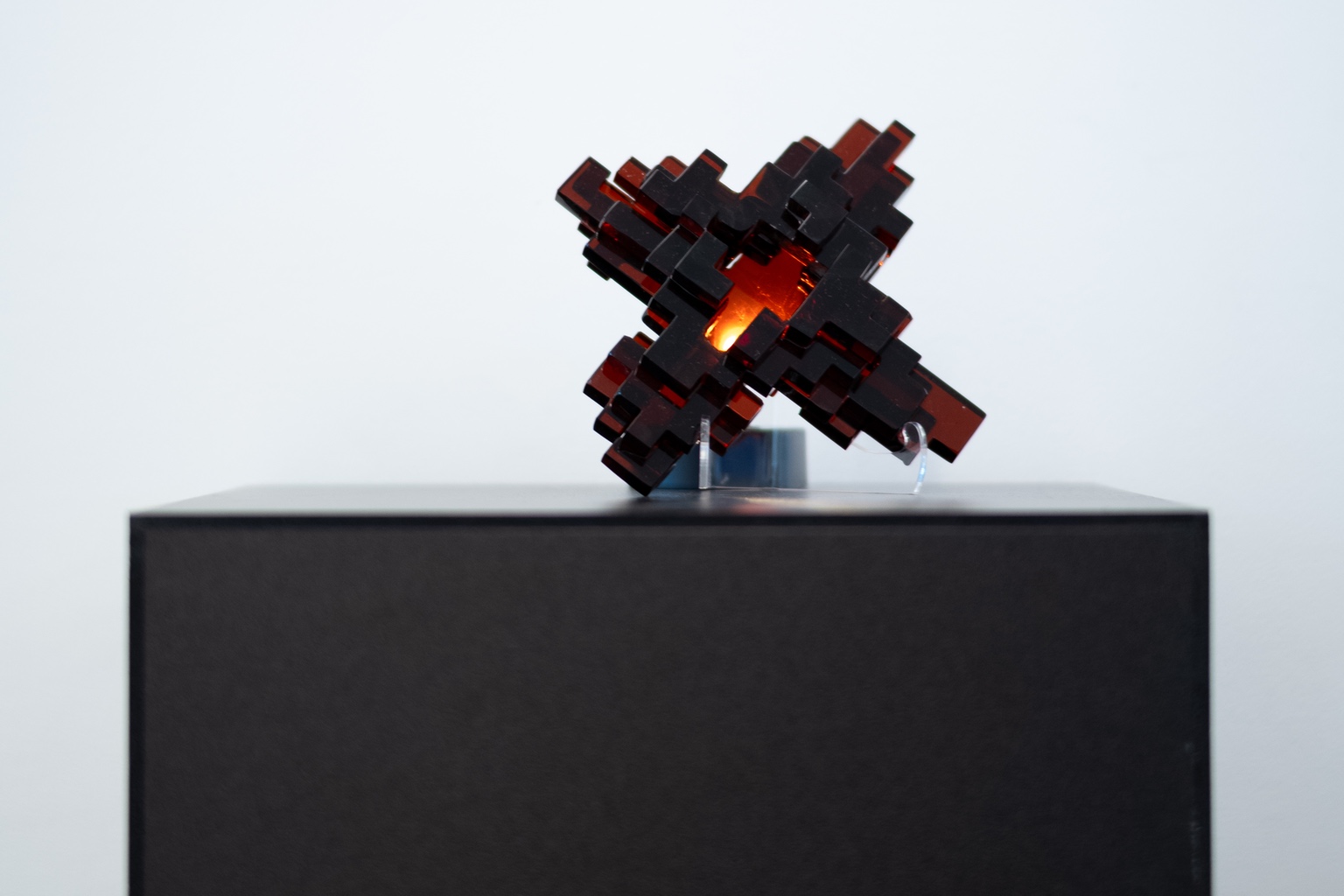

But it turns out that all these achievements have just been the first few chapters of a much longer playbook. Since retiring from the NFL in 2020, Bennett has embarked on another career entirely: designer. After graduating from the Heritage School of Interior Design, he enrolled in an architecture degree at the University of Hawai‘i in Honolulu, where he lives. He also established a design practice, Studio Kër, initially working alongside industrial designer Imhotep Blot, who passed away in 2023. In January 2024, Bennett unveiled his first collection in an exhibition entitled “We Gotta Get Back to the Crib.” And during last December’s edition of Miami Art Week, he debuted an amber glass vessel as part of a series of limited-edition works by a roster of five designers commissioned by Lexus and showcased at both Alcova Miami and the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami.

On a panel that Lexus held at the ICA Miami to mark the launch, architect Germane Barnes (who also contributed to the capsule collection) praised Bennett’s unique combination of star power and integrity. “You can’t miss him — he towers over everyone else. And he’s always going to come up and give you a great big hug every time he sees you,” he said. “It takes a lot of effort to be hopeful and joyful, and Michael always starts with that. I hope that architecture and design doesn’t make him jaded and that his spark stays with him, because he is a deeply caring person.” In conversation with Bennett, that becomes immediately evident. Here, he talks us through the kickoff of his new career — and how it continues his ongoing mission.

Let’s start with the obvious: Football to furniture is not a conventional path. At what point did you decide that design would be your next big move?

- Michael Bennett

I’ve always liked design. Growing up, my brother would say that I had good taste in clothes. And I still see a lot of design in athletics — there is an artistry required to play football, in terms of the architecture of the body and being able to manoeuvre it while still taking care of it. It’s like a structure in itself. There’s also the fact that, I know I’m not overweight, but every time I get into a chair, it breaks. The last time I was in Japan, I broke, like, three chairs. I think about the body a lot — especially the Black body, in terms of the scale and the spaces it manoeuvres through. Moving into design professionally was also motivated by my activism. After retiring from football, I was reading a lot about Booker T. Washington, who spent the late 19th century thinking about rebuilding America for the Black community. That’s when I started to think about design as an act of resistance. How can we change the world? It starts with design.

You’ve described your work with Studio Kër as designed in “joyous opposition to the dominance of Western domestic typologies.” What does that mean to you?

There’s this idea that Black creativity can only come through Black pain. When I go to art exhibits, it’s clear that a lot of the world wants to see Black art as, “Oh, this is what police brutality did to you.” And I think there’s a space for that, but it’s not my space. My space is asking, “What does it feel like to grow up in a family of love? What does it feel like to have Black joy?”

Your designs reference elements of the African diaspora, and your studio takes its name from the Wolof word kër, which means “home” in Senegal, where your ancestors are from. Growing up in Louisiana, were you already deeply familiar with that cultural heritage, or did those references come out of research?

It’s both. I pull from the religious culture of my family, and the sacred parts of growing up in the Black church in Louisiana. But the research is constant, to learn more about myself and my culture. The first time I went to Senegal, I found that it looked a lot like Louisiana — a lot of the culture was the same. Everybody in America is a descendant of somewhere else — all of us are naturalized to America, but we also have something that’s pulling us back to the past. And that’s what Senegal did for me — it pulled me back. As I have found out more about the history of architecture and making and materiality there, it has become this kind of bridge to the swag of being African American.

You initially partnered with Imhotep Blot, an industrial designer who passed away in early 2023. I’m so sorry for your loss. What was your dynamic with him like?

We were two people who both came from the African diaspora — me from Senegal, and him from Haiti — and who care about design and culture. There was a significant communion in the way we think about the connection between past and present through these objects that we want to live into the future. And Imhotep worked at a really dope pace. Industrial design is different from architecture, but at the same time, there are a lot of principles that stay the same. He passed away before Studio Kër could present our first collection, but that show was presented in memory of him.

You debuted that exhibition, “We Gotta Get Back to the Crib,” in January 2024. How did you choose that title?

The collection focused on the essence of Blackness — getting back to ideas of culture, home and family. When I’m making something, I want it to be subtle and elegant, but also urgent. What I am trying to articulate through my focus on African forms is that there’s this fragmented part in the history of America in that traditions from Africa were broken because of slavery. So it’s trying to figure out what’s left over from those fragments to build something new. I feel like a lot of times, design these days is just about observing. You just look at something, like, “Oh, that’s cool.” But when you sit on a chair, does it allow you to have conversations that aren’t just about the chair, and are about the world at large?

Building on that, one of the standouts in the collection is a two-part chair with a fibreglass frame and corresponding body pillow that is named Gumbo. How did that dish play a role in shaping the piece?

For me, design isn’t so much about form leading to function or function leading to form, but narrative leading to form. When gumbo happens, it’s a very communal thing — you put everything into a pot and everybody starts to share. When I retired from football, I tried to think about a word that would push me through the rest of my life and how I think moving forward — and that word was “communion.” I mean that in the sense of spiritual, physical and mental gathering. That’s how I want to see the world, and so everything that I’ve made has been about communion.

In a way, the larger mix of materials in the show also felt like a gumbo — having all these things together and allowing each of them to have their own flavour, whether that’s the earthiness of stone or the warmth of wood. One of the woods that I used is African sapele wood, and I liked that it’s African, but also, my wife’s name is Pele, and she’s like a muse to me. She’s a very beautiful, intelligent individual.

The exhibition was held at the Rebuild Foundation, founded by Theaster Gates. What was it like to show there?

Theaster Gates is one of my good friends, and I like thinking about the way that he is putting things into the perspective that they were always supposed to be seen through. He looks at space in terms of both how it came to be and what it is supposed to be. It takes people plugged into the system to develop the things that they actually want to see in their cities, rather than just having someone else’s desires placed upon them. The Rebuild Foundation is pivotal — it speaks to how I see the world and what I want to see exist.

What was reception to the collection like?

It’s been a mixed bag. Some people think it’s great and other people think that I don’t deserve to be in the design world. But you’ve got to respect losing so that you can love winning. It’s not about fame for me; I already had that. Instead, it’s about finding ways to make an impact. I’m really focused on trying to bring design and all that it has to offer into the spaces I grew up in, so that people have a better sense of what they can be. If you look at my track record politically, and what I stand for as an individual, I’ve never been scared to talk about what I’m supposed to be talking about. That’s just who I am, so I want to continue inspiring people to change.

You established a scholarship for Black designers at the Heritage School of Interior Design, and you and Pele have also set up a $250,000 endowed fund to get more people of colour into the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). What drove those philanthropy decisions?

Again, it’s about systems. RISD is one of the most important design schools, so it makes sense to create more opportunities for people to get skills from there to change their existing communities. When I started playing college football for Texas A&M, I went from seeing nothing but Black and Mexican people to only seeing white people. I became a minority super-fast, and it felt like nothing I did was appropriate. They didn’t like the way I dressed; there was a coach telling me to pull my pants up. And then I realized, I can’t do that. He’s basically taking away what makes me me. I think the more diversity that we allow into those communities, the more that we’ll continue to improve them.

And I think that people are hungry to learn and acquire these skill sets. When I was in Haiti a couple years back, the kids walked 10 miles to school every day. One of them had actually died trying to cross the river in the middle, so the other kids and their families had worked to get a bridge made. Nothing — not even the death of their friend — had kept those kids from getting an education and reaching their potential. It was similar in Senegal. I spent a lot of time working with girls there, and I asked them what they wanted to be. This one girl said that she wanted to become an engineer to devise a better system for ambulances, because her grandmother had died when they couldn’t get an ambulance.

School gives people tools to make better worlds. That’s why I make donations and give my time to these things — because I know the importance of creating an army of thinkers that build a new system. It’s not just about doing the work, but about creating the space for others to do the work. Humans deserve to live in a place with clean water, education, nice parks, access to books — and seeing how people, when they have those opportunities, really rise to the occasion shows me that everyone just wants to exist in a world that’s fair and righteous.

What has your own experience in education at the University of Hawai‘i been like?

It has re-energized me to be around so many young minds. I want to be humble. I know that discipline is important, because I grew up going to practice every single day. I did have to stay up until four in the morning making things. Collaboration and teamwork are also things that were already part of my skill set. I realized that no one thing is designed by just a single person — everything takes a group effort.

You created a limited-edition vessel as part of the Lexus in Design series, which also featured objects by Crafting Plastics, Germane Barnes, Suchi Reddy, and Tara Sakhi (T Sakhi), and a candle by fragrance brand Dilo. Tell me about the concept behind your design.

In America, we talk about the idea of 10,000 hours — but Lexus is built on the idea of the Japanese takumi master craftsman, who spends 60,000 hours devoted to their craft. In Japan, after 10,000 hours, you ain’t even gone pro yet. Having spent a lot of time there, that’s something I’ve always loved about Japan — everything has an elegance to it, even if it’s just the towel folded in your room each night. There’s a meditative rhythm to that repetition. I set out to capture that in a vessel made of amber glass, which became a way to reflect candle flames on a table. I think a lot about ritual: Candles are usually in a sacred space, or to try to set a mood, so I wanted something that would heighten that.

What’s next?

I’m working on several projects right now — a chapel in Seattle and two houses. I’ve also launched a program, Building Motions, that is about bringing art into sanctuary-type secular spaces within communities of colour, and the first edition of that will be in 2025. All of it takes a lot of time — it’s getting kind of hard to sleep sometimes.

When it comes to your furniture designs, have any of your old football teammates reached out to buy anything?

Romeo Okwara, Malcolm Jenkins and Quinton Jefferson have all bought pieces. A lot of my former teammates — and some people I didn’t even play with — have hit me up. [Laughs.] It’s interesting, because I hate the way that everybody in the NFL dresses, so it’s about time they got some style. I think people are always surprised that I’ve been in these two different worlds. Even when I was in Miami for the Lexus in Design launch, some of the other people in the program were asking, “Why do people keep taking pictures with you?” and I had to explain to them, “Oh, I used to play football.” I need to embrace both sides, because it shows other people that they’re not stuck in something, and are able to change if they want to change. I’m 39, and I think a lot of times, people are scared to enter the creative space later on, but some people’s greatest work happened after 50.

Super Bowl Champion Michael Bennett Moves From Football to Furniture Design

The NFL alumnus finds success — and inspires change — in a whole new field.