For too long, the top-down approach to delivering architecture to Canada’s remote communities has largely been an abysmal failure. Much of the problem, to be sure, derives from the astronomical cost and logistics of shipping materials to the North. Formulaic thinking and old-fashioned neglect also figure prominently. Plus, the built landscapes north of the 60th parallel are rarely seen by design journalists and critics, let alone the majority of Canadians. Out of sight, out of mind.

And yet, with their rich heritage and perennial need for housing, northern communities should be the perfect stage for innovation and investment in the built environment. A permanent local community with deep ties to the land is a hugely important bulwark against malign foreign interests — especially now, as climate change widens the Northwest Passage and foreign leaders wear their imperial ambitions on their sleeves. Serving the communities of the North is not just a matter of ethics and legality; for Canada, it may turn out to be an existential issue. Canada’s Arctic coastline — its northern “border” — is 162,000 kilometres long, compared with the 8,900-kilometre-long, highly regulated border to the south. It is newly vulnerable, and its communities require more housing and public buildings than ever before.

But what we think of as the Canadian “North” is huge and varied: almost four million square kilometres with soil conditions, topography, weather patterns and social customs that differ from place to place. There are, in the words of architects Mason White and Lola Sheppard of Lateral Office, “a multiplicity of norths.”

Iqaluit — the capital of Nunavut — offers us a case study on the right and wrong ways to design for the North. As with many other northern communities, this city is informed by both a rich underlying culture and the cataclysm of colonialism and modernity. Once known as Frobisher Bay, it has suffered the consequences of southern-centric planning and building. But recent architectural projects show the value of attentive, locally focused design, when architects are prepared to embrace that approach.

Foremost among the region’s architectural champions are Sheppard and White, who authored the benchmark 2017 book Many Norths: Spatial Practice in a Polar Territory to unpack the complexities of building in such diverse regions. What is pertinent and challenging in a capital of roughly 7,500 people on Baffin Island is a world apart from what is pertinent and challenging in a landlocked hamlet in the Yukon. These kinds of qualitative differences are difficult to address in a meaningful way when housing and public buildings are designed from afar and shipped in as a kit of parts.

Even with those limitations, it’s possible to create architecture that is both meaningful and efficient, when architects take care to work with the local context and stakeholders. Recent examples are the Inuusirvik Community Wellness Hub, by Verne Reimer Architecture and Lateral Office, completed in late 2023; the Nunavut Arctic College Expansion, by Teeple Architects in collaboration with Winnipeg’s Cibinel Architecture; and several buildings by Stantec — a corporate behemoth of a firm not always known for visual excitement — that liven up the treeless surroundings.

Building anything above the treeline is hampered by the dearth of readily available lumber, and building on an island requires everything to be either flown or barged in with strategic (and, in some cases, lucky) timing to the spring melt, which allows water access to certain locales. Constructing on permafrost means the entire building must be built on piles, rather than a conventional foundation, because the incipient heat would begin to thaw the permafrost over time, and the structure would settle into a lopsided mass (known as a “thaw bulb”). Even within the same place, the soil and climate can shift significantly over the years, and, along with the world’s climate, the permafrost is changing, notes Bruce Carscadden. His firm, Carscadden Stokes McDonald Architects, working together with Stantec’s architects and engineers, had to make allowances for that when designing the base of the Iqaluit Aquatic Centre.

The challenges for architects run well beyond engineering pragmatics, notes Vivian Manasc, founder of Edmonton-based firm Reimagine Architects. “The question has to be framed as: How do we build in the Arctic so that the people living in the Arctic are actually excited about sharing the culture of the Arctic?” Manasc served as the professional advisor for the recent international competition for the new Nunavut Inuit Heritage Centre, a process that involved extensive local consultation. Inuk architectural intern Nicole Luke, one of the competition jurors, notes that cultural expression can be embodied in architecture in many ways. The imperative, she warns, is to “avoid key cultural representation that’s just surface-clad, or that can be taken off during the value-engineering process.”

The four finalist schemes — by firms including Lateral Office with Teeple Architects, Bjarke Ingels Group, Helsinki-based ALA Architects, and Copenhagen-based Dorte Mandrup — all addressed the region’s unique geography and lifestyle. The concept by Dorte Mandrup was chosen as the winner. Defined by a curvilinear triple-glazed facade and nestled in bedrock, the dramatic structure seems certain to create excitement, if and when it gets built. (Funding requests for big cultural buildings are stumbling through a rough patch these days.) Speaking to Canadian Geographic, Elder Sakiasie Sowdlooapik, who sits on the board of the Inuit Heritage Trust, explained that engagement played a big part in determining the experience of the building. “When we did the consultations with the community, they told us very clearly that the centre has to represent the landscape and how it’s laid out — that it’s not just going to be cubes,” he said. “It’s going to be something very different — beautiful from the outside and the inside.”

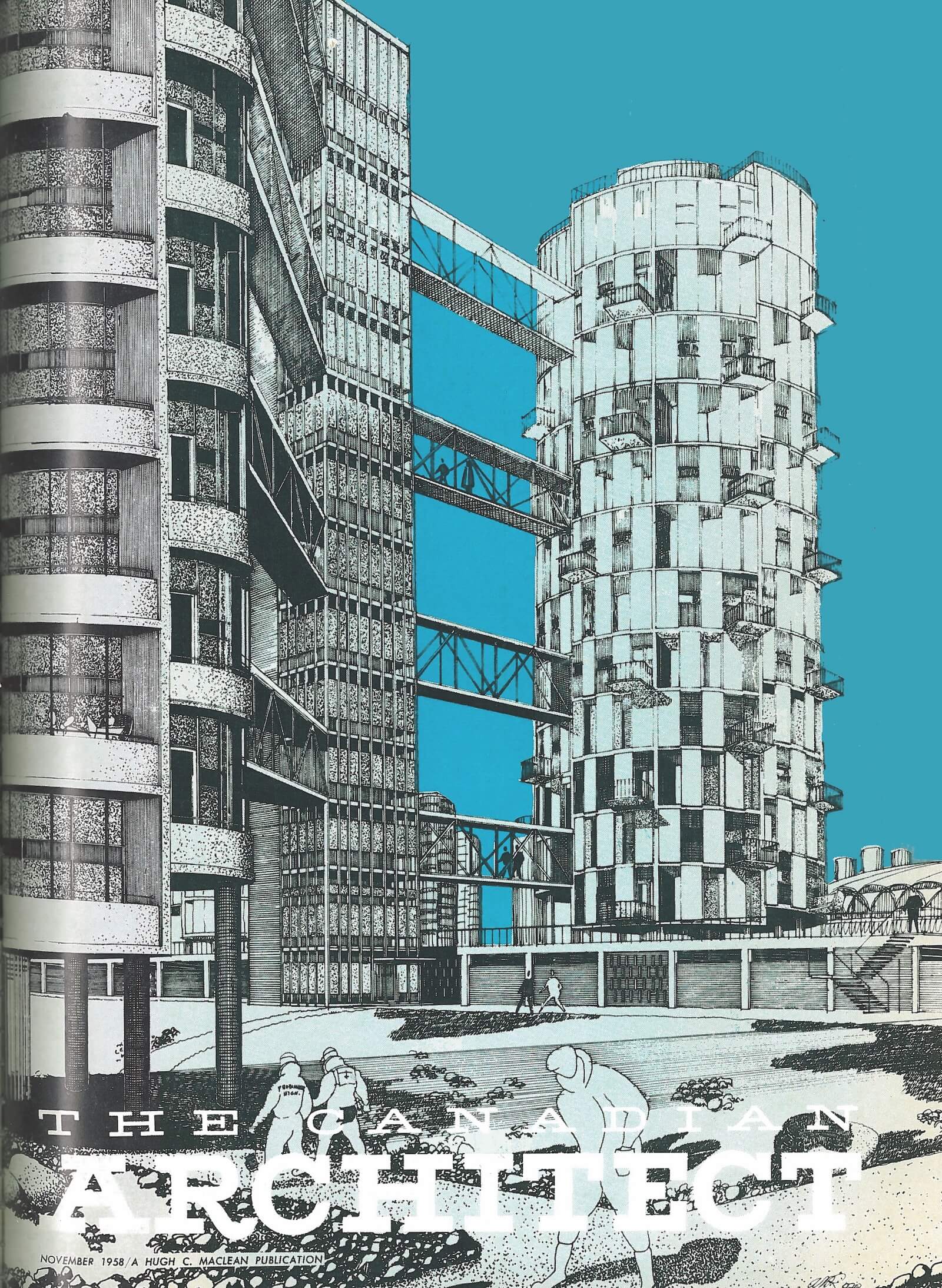

This custom approach is a far cry from the one-size-fits-all building boom launched by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in the 1950s. Under his watch, some 1,200 “matchbox houses” — essentially one-room plywood shacks — were hastily built for Inuit families, a paradigm that unsurprisingly proved to be an abject failure. The following years brought more ambitious design ideas, but from an overtly Euro-Canadian perspective. The federal government’s chief architect devised the futuristic “New Town I, Frobisher Bay,” as Iqaluit was then called. A self-contained mini-community, it was designed to house a thousand people — and all the goods and services they might need in life — within a cluster of interconnected 12-storey towers. As Sheppard and White write in Many Norths, “The fact that these practitioners viewed the environment as inhospitable when seen through the lens of their home climates illuminates a missed opportunity to collaborate with residents and address their specific needs.”

The principals of Whitehorse-based Kobayashi + Zedda Architects are even more critical of the existing built landscape of the Canadian Arctic and the rigid adherence to building codes and standards developed elsewhere. “The modern north was built by military and industrial interests, two organizations that consider community-building and housing as afterthoughts,” says Jack Kobayashi. “We have inherited a completely inappropriate street network and housing typology, which is akin to inheriting an old gas-guzzler from your grandparents.”

I know what he means. During two recent fortnight-long trips to Iqaluit, I stayed at Astro Hill, an architecturally mundane version of the New Town series built in stages from the late 1960s through the ’70s. Astro Hill comprises a mid-rise apartment building, hotel, pub, cinema, grocery store, and smattering of offices and retailers, all connected internally by common spaces and corridors. It is such an anomaly in sprawling, low-rise Iqaluit that it’s known not by its formal name but by its built form: Everyone in town simply calls it the Eight-Storey.

On paper, and to a southern city-slicker, it seems logical: Stay out of the cold, live your whole week — your whole life, even — away from the minus-thirty January climate. By day, I wandered through a grim labyrinth of windowless corridors or stared out the small window of the compact apartment; evenings, we would hear through the thin interior walls our neighbours’ heated conversations or passionate encounters. Throughout the night, the rumble of the elevator down the hall pockmarked our sleep as shift workers and nighthawks returned to the lair.

Building high and close together is a southern-centric solution. Traditionally, the Inuit way of life and inhabitation involves spreading out on the land. So the mid-to-high-rise labyrinth is a dud paradigm for the Arctic. But keeping up with the burgeoning housing demand is a perennial challenge, leading in some instances to haphazard sprawl and, in most cases, to orthogonal kit houses that don’t project a sense of place. “The real priority is more community stakeholder and Indigenous involvement in the design of projects,” says Josh Armstrong, an Iqaluit-based architect with Stantec.

Armstrong worked on both the Iqaluit Aquatic Centre and on St. Jude’s Cathedral, the social and spiritual nucleus for many residents. Ron Thom designed the original cathedral in 1970 as an igloo-like hemisphere furnished by local Inuit artisans, but it was tragically destroyed by fire in 2005. The replacement cathedral — like Thom’s design, based on a dome — was completed by FSC Architects & Engineers (now owned by Stantec) in 2012; the architect of record is Harriet Burdett-Moulton, a Métis woman. Like the original cathedral, its creation involved a critical mass of local involvement and, not coincidentally, it seems well-used and well-loved by the community. For government-issue housing and public buildings, however, that kind of outreach had not been standard practice — until recently.

A concerted effort to engage local end-users early in the design process has been key to the success of the Aquatic Centre and the Iqaluit International Airport (also designed by Stantec), which double as social connectors. “Architecture is evolving in Iqaluit, because that Indigenous voice is pushing for change,” says Armstrong, whose spouse is Inuit — which helps him understand the culture a little more every day, he says.

The most visually striking work of recent architecture is the 2018 Nunavut Arctic College Expansion, whose sculpted roofline evokes the topology of the surrounding region. Inside is a dramatic circular common space, warm wood cladding and a profusion of daylight in every corner. The cafeteria is off the main foyer, in keeping with the local tradition of making food preparation and communal dining a privileged place.

Teeple’s design team sourced materials — pre-finished wood siding, super-insulated walls and triple-glazed windows — based on endurance and insulating quality that would be overkill in the south. And yet cedar, which architects usually avoid as an exterior cladding, given its propensity to rot, turned out to be a viable choice in this hybrid construction; like much of the Arctic, the region around Iqaluit is as dry as a desert. Rainscreen features that would be imperative in the south are useless in the Arctic. Instead, the design team had to configure the piles and massing in such a way that snow wouldn’t gather along the walls. Overall, the high-powered passive-design approach helps to ensure the building stays in shape long after the architects leave town. Six years after its construction, it looks and feels like new.

The greatest testament to the power of good architecture is the stroll from the addition into the original building: Both physically and mentally, my comfort level plunged from high to low as I entered the dim, prison-like corridor of the older structure. “Is that the form you want for your education — a long corridor where people are isolated?” asks Stephen Teeple, rhetorically, “or a more social setting, focused on food, that brings people together?”

As the stakes grow higher for maintaining physically and socially healthy communities along our Northern perimeter, so does the need for regionally appropriate architecture that’s built for the long term and informed by the local context. The region’s historically traditional construction materials have been bone, skin, stone — and snow. All four materials are highly impractical for contemporary building — or are they? Verne Reimer Architecture and Lateral Office designed the newly completed Wellness Hub with scooped-out spaces on its second floor, which serve as balconies in the summer and capture snow in the winter. The design team hopes that the snow that accumulates on the balcony-scoops will help insulate the building. For now, it’s speculation — but it’s low-risk experimentation.

“Whenever you can, smart construction means using simple, basic, reparable pieces,” says White. “When you cannot, it’s smart to use components that can be serviced on a regular basis.” Unlike large cities in the south, where trades and repair personnel are usually easy to find, small remote communities rarely have the skilled technicians living nearby to fix ailing building stock. “What we really need are new ways to co-design and collaborate with local people and allow local leaders to lead,” White continues. “We can’t just say: ‘Well, I just designed this fancy new building, so let’s crane it in and then wish everyone good luck.’ ”

Designing North: A New Generation of Architecture in Iqaluit

After decades of Euro-Canadian planning, Iqaluit is finally benefitting from architecture that boldly meets the context.