A.I. is everywhere: summarizing our emails before we open them, augmenting our Google searches, filling our social media feeds with fake videos that seem uncannily real. For the architecture profession, its promises encompass both the bold and the banal. A.I. can be used to envision fantastical projects at the stroke of a key…It can also sort and read RFP and construction documents. But whether practitioners apply an à la carte approach or embrace vertical integration, the tools themselves are advancing at a breakneck pace. We try to keep up.

This past March, a luxurious development in Slovenia made the design blog rounds. Arranged in a semicircular configuration facing the lake, its white-washed villas all feature an atrium that appears as a dramatic protrusion on the facade — a modern extrapolation of the timber rizalit structures that constitute a heritage Slovenian vernacular. That the homes’ seamless facades and swooping curves, inside and out, seem decidedly parametric is not surprising: The architect, Tim Fu, is an alumnus of Zaha Hadid Architects who recently branched out to start his own practice. More noteworthy is that the Lake Bled, Slovenia, proposal was touted as the “world’s first fully A.I.-driven architectural project.” And Studio Tim Fu is positioning itself as an A.I. architecture firm, one that integrates machine intelligence into the design-to-construction process from beginning to end.

“Our firm is pretty much built from the ground up and structured to harness the power of A.I. and computational design,” Fu says. “We don’t contain ourselves to one tool or one paradigm; we completely use the entire process to our advantage. We collaborate with different companies, including in partnerships with OpenAI, Nvidia and Microsoft.” Still, like most proponents of A.I., Fu stresses that it is a tool first and foremost; it augments the design process rather than taking it over. The designer’s intention is what truly matters.

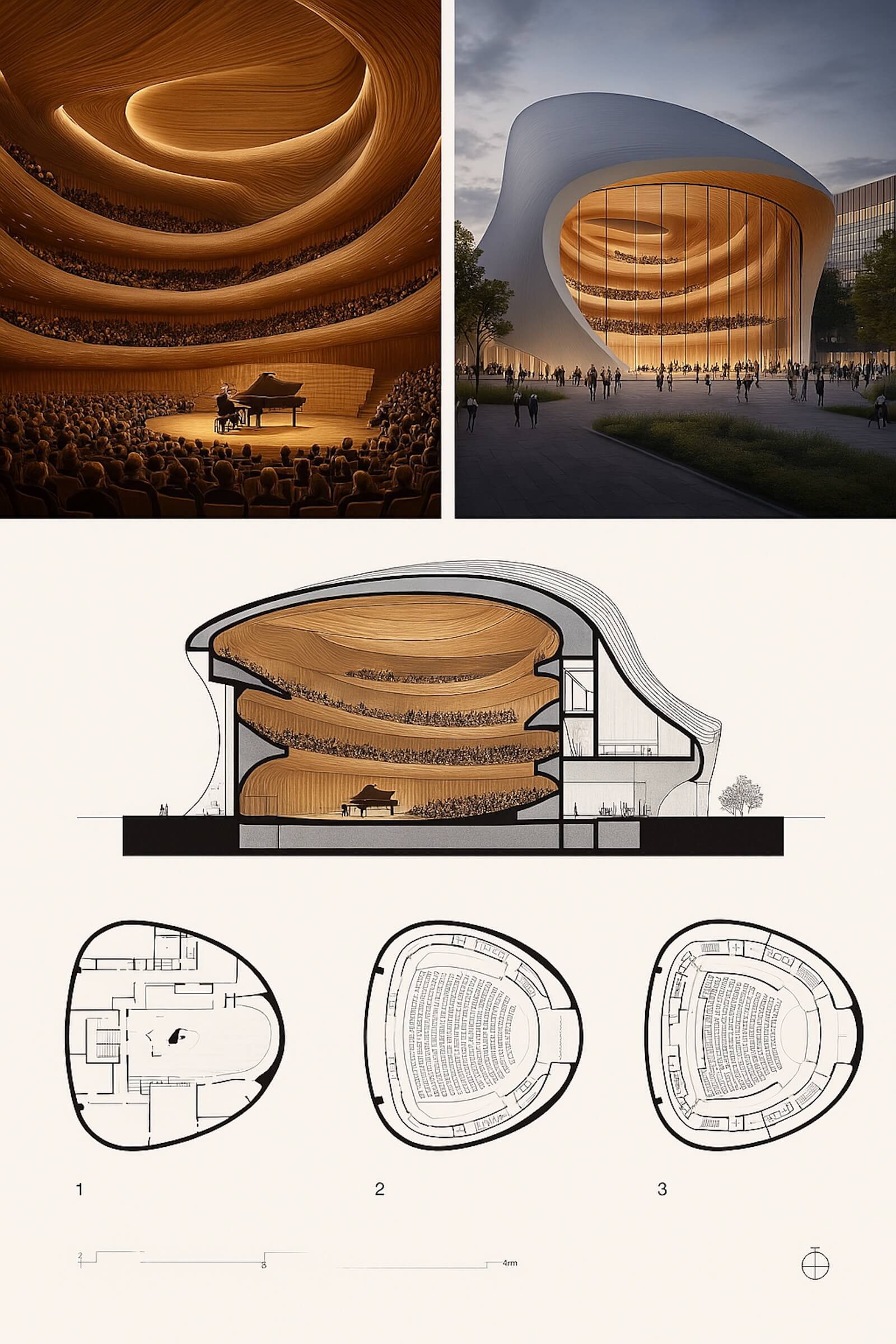

The process, or “workflow,” begins with Midjourney. Almost: “We sketch as well,” Fu explains. “We don’t get rid of that human process.” Released in 2022 and now in version 6.1, Midjourney produces photorealistic results. It uses a large language model (like OpenAI’s ChatGPT), but instead of generating text, it interprets a string of descriptors and — through another A.I. model, called diffusion — outputs a series of visuals in under a minute. Many designers use these visuals for brainstorming and mood-boarding while coming up with a schematic design; they can be fanciful and otherworldly, and tailored to particular styles. “We actually encourage the sort of whimsicality of machine creativity because it further enriches our own ability to create novel concepts,” Fu says.

A prompt can be honed to make the output less random and more in line with what’s in the designer’s mind. For instance, you could begin by asking ChatGPT to rapidly create a chart of parameters for prompts that are then pasted into Midjourney; you can apply code to certain words to amplify them, or blend two or more images to create a new one. You can also load images of your own work into the technology to retexture it, something Fu has done. “We have our own company-trained Midjourney person that uses personalization codes and our own visuals that we input to direct the output much more accurately,” he says. That output, then, can be refined with other imaging tools. “Sometimes, we take the outputs and work with other apps, such as Photoshop. We get it to be completely accurate to the site, and we bring it back into Midjourney to make it more precise. So there’s all sorts of feedback loops; our entire workflow looks like a mesh of different possibilities.”

With the Lake Bled project, historical examples were fed into the rendering process. “We’re mixing these heritage data sets with our own inputs of what future luxury ideas should be and outputting the fusion of these two distinct paradigms.” In parallel, his employees work on resolving the project’s architectonic attributes, which also incorporates A.I. optimization; they end up with a digital model that represents both the design aspirations and the technical requirements. A.I. is also used to produce high-end visuals for marketing and client communications. “You can see the level of quality and detail and the level of accuracy as well. It’s completely accurate to the original 3D model.”

Rapid iterations save time on an initial ideation process that might otherwise take a rendering specialist hours to accomplish. A plethora of products like Midjourney, Dall-E and Stable Diffusion — and now OpenAI, which announced its image generator in March — can create images instantaneously, and many more have been developed specifically for the architecture profession, including LookX, which Fu trained to translate a crumpled piece of paper into a 3D model (a riff on a Simpsons joke about Frank Gehry); Hektar, a “drafting tool for early-stage city-planning”; and Spacio, which fills in the details on building components like facades and is compatible with CAD or BIM programs. Plugged into software like AutoCAD, Revit or Rhino, renderings can take the next steps in the design development stage and undergo performance and sustainability studies, for example. With the help of PlanFinder, an A.I. plug-in for Revit and Rhino, that viable design now has floor plans, for instance; with products like Enscape, it becomes a “3D walkthrough that can be navigated and explored from every angle.”

Fu’s trajectory shows how rapidly the technology is emerging. Only a few short years ago, he was studying nascent Stable Diffusion and large language models in ZHA’s computational research department. “When A.I. came onto the scene,” Fu says, “I grew fascinated with it because it was entering the design room: It wasn’t just about rationalizing geometries or calculating numbers, it was creating design inputs and giving you creative alternatives and solutions.” And while Fu’s practice demonstrates the future possibilities of its vertical integration, most firms are dipping their toes into A.I., taking an à la carte approach to embracing new tools. But even one A.I.-led process can change the game, from the RFP to the final result.

Reworked Workflows & Closed Systems

“Imagine you can hire a very capable person and say, ‘Go to this folder, read everything and understand it.’ Except this person is an A.I. technology. Now that they have become knowledgeable, you can ask them questions exactly as you would ask questions to a colleague, in natural language, and they would provide you answers. But the big advantage of this person is that they never forget and they’re loyal to the company and won’t leave.” This is how Nick Koudas explains the appeal of Workorb AI, the Toronto company he founded with Nilesh Bansal, a fellow researcher at the University of Toronto’s Department of Computer Science. Like Arki Digital and similar tools, Workorb AI helps architecture firms with A.I.-enabled workflow management. Workorb AI’s main product consolidates a firm’s data (including images and design files) in one place (a secure, siloed server), de-duplicating multiple versions of similar documents and selecting the best information within any given one — all with the ultimate purpose of creating a knowledge graph of the entire corporation. This data is then applied to an RFP submission, which an employee of the architecture firm will review and make edits to.

Anyone taking the pulse on A.I. in architecture cites “workflow optimization” as key to understanding the technology’s transformative power at this particular moment. Be it marketing and communication campaigns that require instant project descriptions (as well as rapidly generated images); project acquisition processes that gather, sort and analyze data for RFP proposals, code compliance, site analysis and sustainability studies; or construction documentation and building performance predictions, A.I. tools promise to make both the time-consuming creative aspects and the tedious, repetitive parts of the architect’s job as frictionless as possible. “One big thing that A.I. can do for architecture, engineering and construction is to bring order to their data repositories — giving the ability to go back and look at projects that you did 30 years ago or five years ago or one year ago — and democratizing information access across the entire firm,” Koudas says. It can also streamline “all of these worries about continuity and succession planning.”

For the near future, Workorb AI is developing greater functionality — like site analysis, code compliance and legal workflows that are layered onto the RFP process. There already exist products like UpCodes, an A.I.- powered research assistant for looking up building codes in any American state, and numerous A.I. platforms for gathering and analyzing site data, including Aino, an A.I.-powered platform for “rapid site analysis of any global location.” (One can even imagine a future in which these tools are required for certification. As architect Nikhilesh Korde asks, “Will regulatory bodies eventually require A.I. validation as part of the review process?”)

One area where A.I. will certainly play an important role is sustainability modelling. The study of climate and sun path effects, wind, views and noise can be accelerated by A.I. Cove is an A.I. tool that promises to assess embodied carbon in materials during pre-design, ensure compliance with embodied carbon regulations, and compare structural and material options for the most sustainable choices. Gensler, meanwhile, has developed its own tool: gBlox-CO2. “The moment to make the biggest impact on reducing embodied carbon is during the design phase, but until now, that’s been a) difficult, b) expensive and c) lengthy,” explains Tamarisk Saunders-Davies, the firm’s senior PR manager. “The gBloxCO2 tool assesses the carbon impact of design choices at this crucial early stage, allowing us to partner productively with clients to preserve the design integrity of our solutions while making smart carbon choices.”

Like many behemoth corporate practices, Gensler is developing a suite of proprietary A.I. tools. And it’s doing so with the same purpose of creating, corralling and guarding intellectual property in one place that Koudas espouses. These include gDiffusion, an in-house text-to-image genAI platform “that’s deployed securely inside our ‘cyber walls’ to make sure our design IP and clients’ data are kept secure.” Even boutique firms are following suit. Led by Alex Josephson, Partisans is developing a secure, firewalled A.I. system for rendering based on LoRA (or low-rank adaptation), a technique that helps fine-tune Stable Diffusion models; the Toronto firm is exploring how to train the model on its own comprehensive data set.

Josephson predicts that firms will be able to uniquely tailor their own tools over the next few years — even if these will be expensive to develop. “The cost is enormous. To do this properly, people need to be able to dedicate time on a consistent basis,” he says. “Where does the money come from to pay for this experimentation? It comes from whatever profits exist and/or represents marketing time. But the reality is that the leaders in terms of using this will have to be very focused, with a small team of passionate experts. Building that team is our next step.”

Blueprints to Site

If A.I. were to deliver on its much-vaunted promise to rid us of drudgery, meanwhile, it might do so in an area of architectural document preparation called “takeoff.” Takeoff is the term for extracting information from a set of architectural drawings to find out, for example, the net area of a building and the number of walls and floors inside it, down to how many toilets and sinks are dispersed throughout. Doug Dockery, the chief technology officer of ConstructConnect, describes how automation is transforming this hours-to-days-long task that often involves counting — either manually or with mouse clicks — individual icons on a blueprint. “It happens instantaneously. And that’s important, because as new people come into the construction industry, it gives them a way to check what they’re doing,” he explained in a presentation at Toronto’s Buildings Show in December.

Besides ConstructConnect, numerous apps exist to make marking up a floor plan for construction or speccing purposes much easier, including Swapp, Hypar and Blueprints AI. Autodesk, of course, also provides this A.I. functionality — as well as a slew of others, in apps including Forma (which provides real-time analysis for wind, noise and operational energy) and InfoDrainage (for flood mapping). Also at the Buildings Show, Pat Keaney, Autodesk’s director of product management — intelligence, highlighted A.I.’s ability to mitigate risk in the construction zone. “Applying A.I. to construction, we want to leverage analytics and automation to improve decision-making, to enhance productivity and reduce risk,” she explained.

One way that Autodesk is doing this is by capturing the myriad data on a single construction zone photograph. On job sites, contractors and design teams take thousands of photos. “People take a photo and attach it to an issue, for example,” Keaney says. “But that photo could have really interesting information about a safety problem. By automatically tagging those photos, when you’re trying to find them later, you can search them by things like building systems, building components, electrical et cetera.” For any issue, A.I. can read, evaluate and categorize it — then analyze it for risk. “We talked to project managers building an arena, and they’re like, ‘I have 10,000 issues open at any point in time, literally, on this project. If I was going to review all the issues, that’s all I would do. I would never leave my desk. I would just be the issue-reviewer.’ ”

The numbers drive home the point: According to Keaney, bad data costs the construction industry US$88 billion annually; 95.5 per cent of construction data goes unused; and general contractors spend 35 per cent of their time on non-productive activities.

Moore’s Law on Steroids

Artificial intelligence in all of its guises has infiltrated our lives over the past decade. You cannot discuss A.I. without surveying the risks it poses: to our jobs, to intellectual property, to privacy, to the environment. And that is before we even begin to discuss the existential threats it poses to our very selves. Like any nascent technology, bad actors are the first to exploit its features. Deepfakes have only gained sophistication since that Midjourney-generated photo of Pope Francis in a puffer coat and the first reports of people being defrauded by ransom schemes using convincingly frantic calls from “kidnapped” family members.

If new technologies have contributed to our growing distrust in the media, even satirists could aggravate real-world tensions with a badly timed joke: As soon as Solo Avital shared an Arcana AI–rendered video of Donald Trump and Benjamin Netanyahu tanning themselves on the beach of a Trumpified Gaza Strip, the U.S. president himself endorsed it — it effectively validated and glamorized his abhorrent vision. A.I.’s realistic representations add to the mayhem of our increasingly unstable collective sense of reality.

In architecture — as well as in product design, landscape architecture and urban planning — machine learning has numerous advantages but raises many questions. If most architects are at the point now where they believe that A.I. is just a tool, like others before it (from CAD to BIM to 3D printing), they need to also grasp that A.I. is developing at a breakneck pace, that machine learning has infinite poorly understood possibilities, and that they play a role in its legitimization as a design process. They also must acknowledge that, yes, it will eliminate jobs.

Large language models like ChatGPT, which scraped the Internet to create many of these tools, immediately raised copyright concerns. While it aggregates information from various sources, sometimes (if the subject is esoteric enough) a Google synopsis will include exact wording from a single journalist’s copyrighted work — without citation. The same concerns apply to the other creative industries, including art and architecture. A.I. has been used to duplicate artists’ works for purposes unsanctioned by those artists (to wit, the ongoing controversy around animations that resemble work by Studio Ghibli); and, trained similarly to ChatGPT, Midjourney and comparable text-to-image apps often produce results that riff too closely on photography or renderings of architects’ existing works, spitting out uncanny-valley simulacra. (Full disclosure: I used an A.I. tool, Otter.ai, to transcribe my interviews, and I read Google A.I.’s synopses of issues surrounding A.I., before doing deeper dives. Other forms of A.I. may have infiltrated my process.)

If you create an image on Midjourney, who owns it? Under the law, you cannot copyright a simple rendering because it was generated by a computer, not a human, yet some — including architect Patrik Schumacher — are positing that “sufficiently expressive” prompts could arguably constitute IP. Everyone should be wary of feeding their own work into an open-source platform, where it could become a reference point for a future user’s prompt. (And new workflows — whether automated by A.I. or not — need also incorporate checks and balances to protect against IP leakage.) The true-to-life rendering capabilities of A.I. also present ethical questions in the specific cases of architecture’s relationship with the design press — and with the public. A sexy image can sell a project to the world long before its completion; A.I. further problematizes this with seductive images that rival photographs and look better than the real thing, if and when it gets built.

It can also lead to an increased flattening of architectural language, through the diminishing returns of derivative results. “Aesthetics will be driven by those who have commercialized them the most first,” Josephson says. Almost as soon as OpenAI’s text-to-image functionality was announced, Partisans released images created with it, as well as the corresponding floor plans. While the firm has never shuddered before new technologies, it is exploring A.I. with a critical eye. Josephson worries about the implications for architects’ jobs; he’s also wary of the opacity of open A.I. platforms — which he says prefer “certain firms’ works over others” while keeping us from “looking behind that curtain” to better understand how they were trained — and “the alluring but vapid images” they churn out. It becomes a game of finding “the fluke,” the one image among the dozens conjured that actually triggers a new insight. And those floor plans? They’re just as illusory as a lifelike image that only exists on our screens. “If Jean Baudrillard is up there, he’s laughing at us,” Josephson says, referencing the French sociologist who warned of symbols superseding reality. “The software is able to simulate advanced architectural detail, but it is still a fantasy.”

One of the gravest concerns, however, surrounds the sheer amount of energy consumed by the complex data processing required by A.I. The New York Times recently reported that OpenAI, the maker of ChatGPT, is planning to build five data centres that together would consume more electricity than Massachusetts’s three million households. In Brazil, where energy poverty is rampant, contributing to the precarity of livelihoods, 46 new data centres are either under construction or being planned across the country, and 60 are already in operation.

The Canada Energy Regulator forecast that the energy consumption of data centres, which number almost 240 across the nation, will double by the end of 2026 as investors are drawn to the country because of its relatively low energy costs and temperatures. The problem lies in the heart of the tech: the complex, interconnected information-crunching processes performed in A.I. are undertaken by supercomputers powered by up to 100,000 chips. One bright spot, surprisingly, is DeepSeek: The ChatGPT competitor developed in China uses far fewer chips than existing models. (The self-censoring A.I., however, raises other concerns: Users have found that answers to political questions seem to be edited in real time for compliance with state-sanctioned messaging.) Where there’s a problem, there’s a design solution being conjured to fix it. While the computers are the main energy-guzzlers, architecture firms designing data centres are aiming to create more sustainable buildings to house them.

Gensler is one of them. Kaley Blackstock, the sustainability director of Gensler Phoenix, acknowledges the conundrum. “A.I., smart devices and advanced technologies have accelerated the demand for data processing, projecting a global generation of 2,100 zettabytes of data by 2035,” she has written. She notes, as many do, that part of the answer to designing more energy-efficient data centres is achieving a PUE (power usage effectiveness) of 1. This means that a data centre should only consume the exact equivalent of power required for computing; no extra power should be consumed in cooling and other mechanical systems. Carbon-neutral architecture to the rescue.

Jackson Metcalf is the critical facilities leader at Gensler, where he works across the U.S. to design data centres both in suburbs/exurbs and city cores. “It’s not uncommon for a campus to be planned now in the two-to-500-megawatt range, and campuses exceeding one gigawatt are absolutely in the pipeline too,” he says. “That’s what we’re seeing with the hyper-scale cloud computing, whether it’s on the expert side or on the co-location developer side.” Metcalf explains that these data centres are large but not wasteful consumers of energy. That would be akin to “lighting a match to lots of extra dollars to pay for power.” He does see a role for design in making the buildings themselves sustainable, especially when it comes to repurposing vacated office campuses and headquarters in the suburbs. “If you have a really large corporate campus, a lot of times those buildings were built pretty well. If you removed every other floor in a typical building, you can have 30-foot floors, and double the amount of structural capacity to meet the needs of a new data centre.”

Future Developments

“We’re at the point where A.I. can be very precisely driven by a team of professional architects, landscape and interior architects, consultants, and everybody who has a goal that needs to be met. They can drive the A.I. in this direction, and that is where it goes from a creative randomizer into an intentful tool,” says Tim Fu. But even he concedes, “Right now, though, the technology is moving too fast. We have gained a lot of insights in the last two weeks alone. There’s going to be a huge disruption coming forward.”

For architects, the uses of machine learning tools can be seen as a natural progression, from hand-drawing and tedious task work to the “real-time breakthrough” of rapid rendering and workflow enhancement. In this positive view of A.I., those who fear it could come for their jobs might be reassured with a platitude like “Your job won’t be replaced by A.I.; your job will be replaced by a colleague who can use A.I. to do your job better” — a sentiment that recurs in many anodyne takes on A.I. But the effect in the long run will be revolutionary, the future applications mind-boggling. And some are arguing for complete capitulation. Writing in Common Edge, Eric J. Cesal encourages architecture firms to reorganize their entire praxis around A.I., rather than overlaying A.I. tools on their existing workflows — and he provides such examples as adopting real-time project phasing where A.I. can automatically flag budget or siting concerns, or developing a client avatar that can stand in for the real thing to answer presumptive questions along the way. “Optimizing for A.I. won’t guarantee success in the A.I. era. But not optimizing for A.I. will almost certainly guarantee failure,” he avers.

Predicated on language and pattern recognition, artificial intelligence has already moved beyond both today, Fu explains. “It has spatial understanding. It’s able to conceive ideas. It’s able to understand the correlation between our language, how we detect concepts through language into physical manifestations. It’s able to generate codes and represent concepts in multimodal: image, video and 3D modelling. As that happens, it starts to really take over.” Of course, Fu’s firm is going all in. Where others are treading lightly or might eschew specialized A.I. technologies in their architecture work altogether, Fu is latching onto the reins. “We know that the future is going to go directly from concept to output, and we are patching it together into a closed loop. So that’s an inevitability, and we want to be the first to pioneer that project.”

A.I. in Architecture: The Shape of Design to Come?

How architecture firms are adopting A.I. tools and entirely A.I.-driven workflows – evolving both how and what they design.