Last month, the most famous traffic roundabout in one of the most famously car-dependent cities in America was closed to vehicles and transformed into a public space for people. For the third year in a row, the seasonal SPARK on the Circle returned to Monument Circle in Downtown Indianapolis. In 2025, however, the short-term park has a dual purpose — as a pop-up public space and as a testing lab for a long-term vision of Monument Circle.

The aspiration for SPARK is to show that there is a greater role for temporary placemaking — also known as tactical urbanism, DIY city-building, or pop-up urbanism — both as an opportunity to bring meaningful design to the placemaking process and as one of the most useful approaches communities and designers can utilize to drive long term transformation of public spaces.

Since the turn of the millennium, temporary placemaking projects have increasingly sprung up in cities and towns across the world, popularized through welcome efforts like Park(ing) Day, Ciclovía and Open Streets. To the extent that design is part of the experience, these initiatives often come with a tell-tale aesthetic; think off-the-shelf plastic lounge chairs, jersey barriers, shipping palettes, astroturf, and maybe a giant Jenga set, or streets playfully scrawled with sidewalk chalk. While such efforts have been transformative in advancing conversations about events and temporary activation in communities, they often miss out on latent opportunities to catalyze and test ideas about designing long-term physical spaces that people will love for generations — permanent public parks, plazas, and public spaces that reflect the unique social identity and histories of communities.

As landscape architects, we’re increasingly emphasizing an approach that integrates innovative short term design, activation and research with traditional long term planning and design — as seen through our projects like Monument Circle. Our work spans from long-term, built landscape projects to short-term activations, temporary installations, and community engagements. This holistic approach is intended to ensure that the public spaces we create are shaped by research, history, and meaningful community input. What does this design process look like? What can the long-term impacts be?

In experiential placemaking circles, there is a chronic wariness over the role of design — and a particular aversion to emphasizing design of programming. In our view, however, the best projects balance both. To underplay design is to overlook an integral part of making any space — whether temporary or permanent — feel unique and “place-ful,” rather than generic and placeless. Yet, to devalue programming undermines the necessary role of actively bringing people together. Great public spaces need both beautiful, functional design and fun, reliable programming.

Throughout our work, we aim to bring design process to the placemaking process — even if a pop-up project has a tight budget, small scale, and expedited timeline. We start by digging into history — archives, old maps, local stories — and then, guided by community input, we sketch ideas that feel genuine. We develop design options and after lots of back and forth, iterating a preferred final vision for a space. Design is not just about the aesthetic; it’s about making a space feel specific, intentional, alive. It’s about the details — colour, materials, shape — that tell a story.

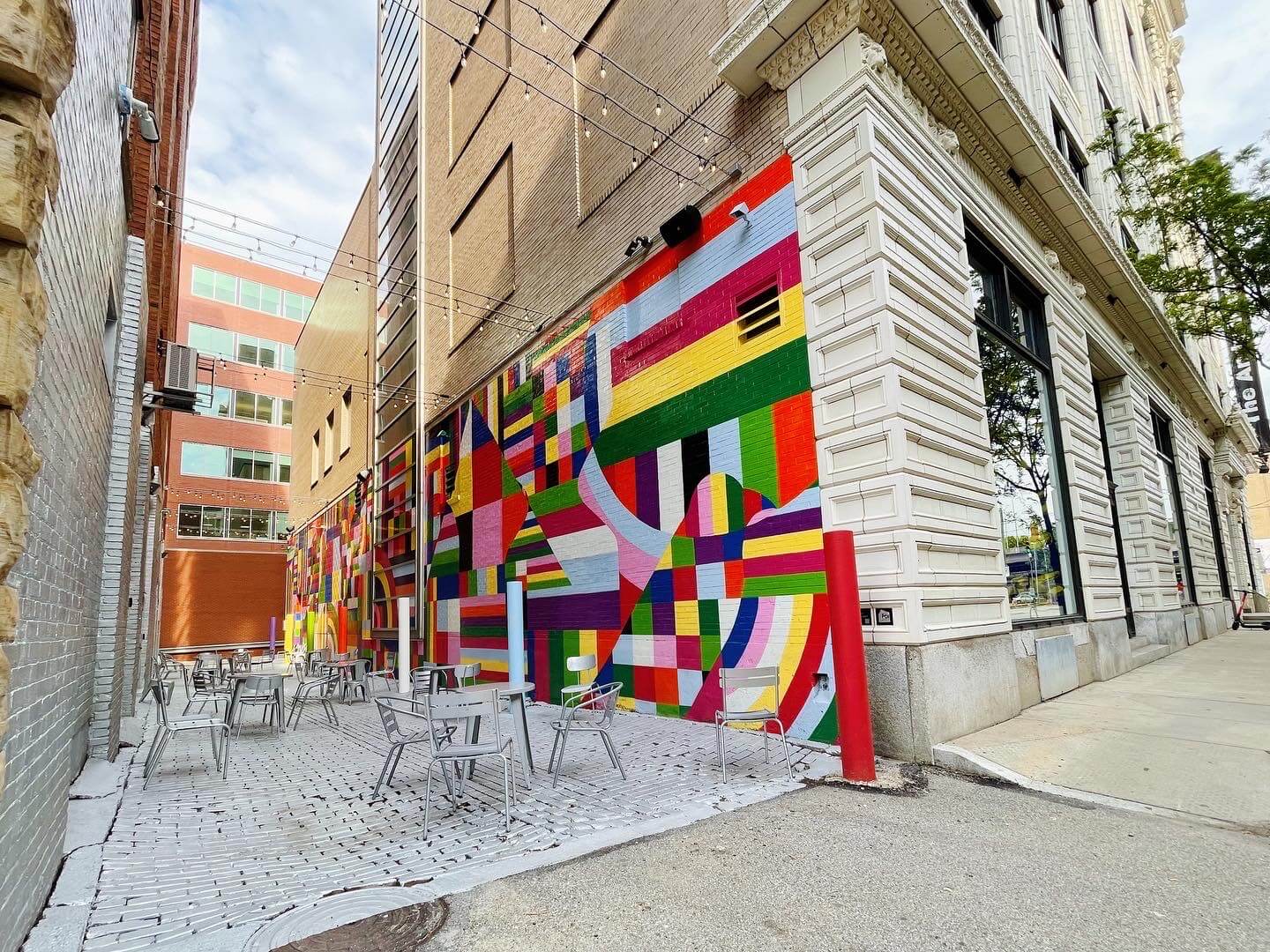

In Pittsburgh, we worked with The Andy Warhol Museum on the identity of the public realm of The Pop District, a newly formed arts district anchored by the Museum. We poured through historical images of The Factory, Warhol’s experimental art studio in New York and dug into Warhol’s landscape focused art. We tested multiple design ideas, including how to deconstruct Warhol’s Flowers series into 3D inhabitable landscapes and how to replicate the silver backdrop of The Factory outside on the streets. We workshopped ideas with museum leaders and local and national artists, and ultimately co-designed an approach called “Silver Streets.” Drawing on Warhol’s ideas of the colour silver as the perfect neutral, we painted the sidewalks, a parking lot, three sides of an alleyway, and outdoor furniture silver. The Factory’s silver walls, tin foil ceiling, and spray painted furniture were the backdrop to the colour, art, and people in Andy Warhol’s orbit. Today the public realm of The Pop District is a luminous tribute to Pittsburgh’s cultural identity as Warhol’s home city. This is the kind of placemaking that — we hope — feels rooted in place.

For the temporary design of SPARK on the Circle in Indianapolis, we collaborated with Big Car Collaborative, City of Indianapolis, Downtown Indy, and Indiana War Memorial Commission. We researched Monument Circle’s history in the 1800s as a shaded park and green space before it became today’s iconic vehicular roundabout. We took stock of previous programming efforts, availability of existing outdoor furniture, desire for food, drink and kid-friendly spaces, and requirements for traffic safety. Collectively we were inspired to create a shaded, green, park-like urban space on the existing red brick road with ample space to support daily activation and events.

While we designed the physical space with relatively inexpensive and readily available materials, including astroturf, planters, and lounge chairs, we riffed off the geometry of the Circle and customized the astroturf into oversized circles to define zones for different activities. A beer garden, performance area, and kids playground each occupy a different circle and create circular rooms within the Circle. We also colour drenched the pop-park bright green to reinforce the idea of bringing green space to the grey city centre while referencing the past; before the automobile dominated American life, Monument Circle was known as Circle Park.

Most urban design processes follow a familiar script: concept design, fundraising, construction documentation, construction. While our goal is to create permanent places that people love, the traditional process can be slow and expensive. Momentum for projects often wanes between phases. In our work, we have found that the practice of placemaking can be integrated into the traditional design process. Where traditional design processes can fail to ignite public imagination, a placemaking approach to city building offers a freedom for experimentation and allows communities to test ideas before making permanent public-space investments. Placemaking as part of the design process helps to build momentum in the short-term for change in the long-term. We’re not just designing for the future, we’re testing it in the present.

The tenets of temporary placemaking — immersive, fun, short-term — provide inspiration for how to engage the public in the process of design. As designers developing public parks, downtown plazas, and city streets, we’ve started to integrate placemaking phases into our design process. For long-range design projects, the public is expected to wrap their heads around large conceptual ideas by reviewing two dimensional plans and perspective renderings. By integrating placemaking into the design process and letting the public experience one-to-one scale proof of concepts of future designs, we can observe and get feedback on design ideas in real time. We can see how people respond and tweak the design. We can generate momentum for longer term projects more quickly and can make complex design ideas feel more accessible.

In addition to bringing the public through the design approach, a tactical approach can make it easier to build support among stakeholders, local policymakers and funders. Placemaking models invite stakeholders to connect with a future investment, albeit at a smaller scale and with less risk. These projects can also make it easier to navigate bureaucracy. No endless meetings, just real, immediate feedback. In Boston, we were hired by the municipality to transform Birch Street, a short one-way street into a pedestrianized plaza. We incorporated a placemaking phase into our design process and installed a six-day pop-up version of the design to experiment with conceptual ideas and get feedback from the public in real time.

Witnessing public and local business’s positive reception and engagement on the street allowed the project to fly through what would have normally been a drawn out and arduous permitting process — we invited the fire marshall to see the project in person to answer questions and concerns and witnessed the head of the Public Improvement Commission utilizing the space.

In the case of Monument Circle, the design of SPARK has catapulted conversations about closure of portions of the Circle to cars into the public consciousness of Indianapolis. As the former New York City Department of Transportation commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan often stressed, a tangible — if temporary — change can be far more impactful than meetings and conceptual renderings. “Instead of arguing and debating, try something first and give people something to experience,” said Sadik-Khan. “When you adapt a place and adapt a space, people adopt it.”

Public enthusiasm and both qualitative and quantitative evidence shows that SPARK is working — over 70,000 people visited the space last year with over 270 programming elements taking place. Pedestrian foot traffic is up 25 per cent within the Circle. The project has kickstarted conversations about what the longer term future of the site could look like and served as a test case for a wider South Downtown Connectivity Plan.

With the closure of Monument Circle for SPARK this summer, we are continuing to observe and document how people are using the pop-up park, working with the City of Indianapolis and parters to gather input and build consensus. This work is informing the creation of a long-range plan to transform the Circle. With the support of the Emerson Collective, we aim to develop an aspirational, human-scaled public space in the heart of Downtown Indianapolis. We hope to turn a quick spark into a permanent glow.

Like the experimental spaces themselves, our design firm is continuing to iterate what a placemaking approach within a design process can look like. In our own small way, we hope that the work we’re doing is helping make the case that temporary placemaking should incorporate greater design rigour and that the practice of landscape architecture should celebrate more play and experimentation.

Nina Chase and Chris Merritt are co-founders of Merritt Chase, an Indianapolis- and Pittsburgh-based landscape architecture practice dedicated to creating public spaces that connect people, culture, and ecology across Middle America.

Lead image by AJ Mast.

Can Pop-Up Urbanism Spark a Lasting Design Legacy?

Merritt Chase co-founders Nina Chase and Chris Merritt argue that temporary placemaking should catalyze a deeper design dialogue — and inform lasting change.