Toronto’s Dufferin Street ranks among the city’s most stress-inducing arteries. A messy ballet of honking cars, endless potholes and overstuffed buses meets an eclectic landscape of houses, apartment towers, tightly packed strip malls and sprawling shopping centres. Follow it just 40 kilometres north, however, and the frenetic city dissolves into an entirely different setting. Messy urbanity turns bucolic rolling woodland, and the street itself gently morphs into a rustic gravel road. All the way up at 17000 Dufferin Street, the five-digit address sits among foliage so thick it nearly obscures both the side road and the signage announcing the campus around the corner. Past the leafy branches, you can just about make out the lettering: University of Toronto — The Koffler Scientific Reserve.

Down a smaller gravel path, a hilltop clearing reveals a sharp pair of pitched-roof volumes connected by a single-storey base. The composition is at once boldly novel and quietly contextual. While its blackened wood, sleek glass and crisp angles convey an assertively contemporary aesthetic, the complex does not feel out of place among the region’s agricultural vernacular of wooden barns and farmhouses. On a site that’s home to an established post-secondary research hub, the new 2,680-square-metre mass timber building combines a student dormitory with a small classroom and a dining hall and common room, setting the stage for the diverse fieldwork taking place in the wetlands, forests and grasslands that make up the university’s 348 hectares.

Designed by Toronto’s Montgomery Sisam Architects, the dining and operations centre at the Koffler Scientific Reserve replaces a dated cluster of buildings previously used for ad hoc dorms and research facilities. Once a series of agricultural plots, the site was first assembled as an equestrian centre in the 1950s, which was then donated to the university by philanthropists Murray and Marvelle Koffler in 1995. “It was never great agricultural land, but it proved to be a fantastic place for scientific research,” says Montgomery Sisam principal Bob Davies, highlighting the wealth of biodiversity on Dufferin’s doorstep. While the setting was exceptionally well-suited for learning, the same couldn’t be said for the buildings. “There were three old barns there, none of which were intended to serve as student housing or educational spaces,” says Davies. “It wasn’t working anymore; the buildings started to need increasingly significant repairs, and it was also really difficult for the university to monitor and maintain livable conditions.” It translated to a seemingly simple brief for new student housing with an emphasis on shared social spaces, as well as a small on-site classroom.

Although removing the existing buildings cleared the way for a reimagined campus, the ecologically sensitive landscape meant that all new construction had to fit within the footprint already disturbed by previous development and demolition. “Our intervention was limited to the site of the three old barns and an adjacent asphalt parking lot, which had been in very rough shape itself, that was also removed,” says Davies. Moreover, the highly seasonal nature of the university’s research programs — and its variable student population — presented an additional challenge. “Every summer, the numbers swell as undergraduates join the group, which is otherwise mostly graduate and doctoral researchers.”

In lieu of a larger (and more carbon-intensive) centralized building that would remain at least partially empty most of the year, the university opted for an unconventional hybrid solution. The main building houses 20 students and the adjacent cluster of 20 bunkies accommodates up to another 40; the shared amenities in the main structure — like the kitchen, bathrooms and living spaces — are generously oversized to support a larger summer population and foster an inviting, convivial dynamic year-round.

“The footprint itself was limited, but the open natural surroundings gave us freedom to orient the building. In the absence of existing infrastructure like a road or other buildings to relate to, we decided to align the structure with the cardinal directions,” says Davies. The gesture served several goals. For starters, the direct southern exposure allowed the building to maximize on-site photovoltaics. This in turn shaped the two prominent shed roofs that define the formal expression. “We knew we wanted solar panels, which yields a certain angle based on our line of latitude to optimize energy production,” Davies explains.

Of course, an efficient and carbon-conscious building takes much more than solar panels. While power generation influenced the angular forms, the project is just as profoundly (albeit slightly less conspicuously) shaped by the movement of light, air and heat. Framing the common room’s pitched elevation, a flat roof and sunshade is carefully positioned to welcome the warming winter sun while mitigating uncomfortable summer rays. Inside, the airy common space is contoured to move warmer air out of the building; an automated window system opens to release heat through the tall clerestory windows. Constructed with glulam columns and beams with a tongue-and-groove roof, the building is a hybrid of mass timber and conventional light-frame wood construction. The partially exposed glulam structure is complemented by simple, low-carbon finishes of gypsum board and plywood veneer, which emphasizes a connection to nature; these panels can be easily removed to allow for swift maintenance and repair work.

The passive strategies continue below grade. A ground source heat pump harnesses stable subterranean temperatures to warm and cool the space above, circulating fluid through deep underground pipes to absorb heat from the earth during the winter and return it in the summer months. The massive earth tube is an even simpler system: Outdoor intake air is cooled or heated underground before being released into the building. According to research by Natural Resources Canada, such systems can warm winter air by about 14.3°C and cool summer air by nearly 6.8°C. “The earth tube is really an ancient technology,” says Davies. “Greeks and Romans built these.”

Yet while the earth tube and the careful solar configuration harness technologies that date to antiquity, such strategies are innovative in a 21st-century building culture that remains dominated by carbon-intensive mechanical systems. According to Davies, learning from history shaped the whole of the project. “There’s not much in this building that’s new,” the architect tells me, noting that the individual volumes were similarly inspired by agrarian forms. While the dark wood facade and pitched roofs evoke the barn, the inspiration runs deeper, driving the design’s low-carbon principles. “In a barn, you typically have a stone base, where animals are kept in the winter, and then the upper part is where hay is stacked to dry. But what happens is that the heat from cows and pigs and horses rises into the hay, with a risk of spontaneous combustion,” Davies explains. “Over time, they learned to build barns with gaps between the upper boards, bringing in natural ventilation and letting the heat escape. There’s a science to it all, but also a beauty.” The new “barns” work the same way. At the Koffler Scientific Reserve, the glazed gaps in the wooden cladding open up to the automated windows in both the dining and dormitory volumes, adapting vernacular principles to a contemporary context.

Inside, this translates into surprisingly soulful spaces. In the open dining hall and refectory, the simple wood cladding and carefully proportioned window openings create an energetic yet calming ambiance, while the tall, slanted ceiling fosters an almost cathedral-like setting. It is a casual, rustic, ordinary, uplifting and profoundly sophisticated space. In my estimation, it is already one of the canonic rooms of 21st-century Canadian design. At the end of the hall, a small classroom provides a traditional learning space to supplement fieldwork.

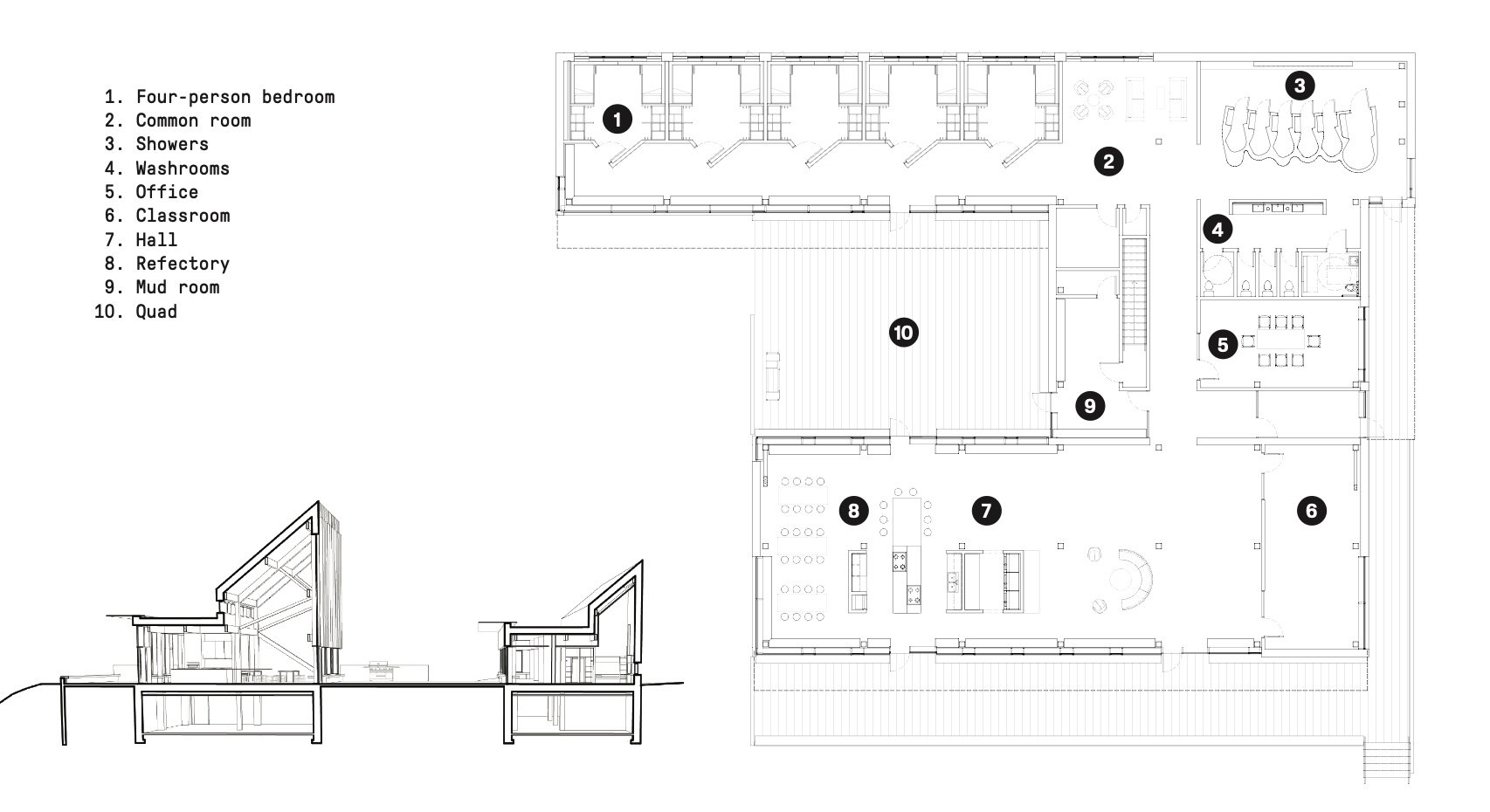

The tall commons volume overlooks a courtyard; dormitories and bathrooms are located on the other side of the quad. In between, a central wood-panelled circulation corridor is paired with a generous mud room. On the far side of the C-shaped building, and tucked into a corner that summertime bunkie residents can access via a separate entrance, are the shared bathrooms.

Here, the visual language of light wood and linear geometry gives way to a sinuous white composition inspired by the form of an amoeba under the microscope. Down the hall is a row of five bedrooms, each boasting four beds; every suite is fronted by an angled entryway that creates a subtle but palpable separation between public and private zones.

The residential hallway is framed by a long bench that hugs the windows. On the other side of the glass, another bench embraces the courtyard, contouring the whole building in welcoming, sociable seating. This gesture — an elegant Montgomery Sisam signature used to similarly good effect downtown at the University of Toronto’s Myhal Centre for Engineering — dissolves the hard boundary between indoor and outdoor space but eschews the more common (and typically less effective) strategy of simply glazing the entire ground level.

Outside, Montgomery Sisam’s 20 little bunkies echo the building’s angular blackened wood aesthetic in miniature. Each of the structures — which were small enough to forgo building permits — is topped by a solar panel, while the simple interior comprises bunk beds and a compact desk. The bunkies themselves are arranged in a rectilinear pattern, quietly repeating the courtyard form within a natural setting.

For Bob Davies, this play of scales forms the project’s philosophical core. Standing in nature’s courtyard, surrounded by bunkies, he explains the project’s genesis. The site — which offers prime star gazing — is at once a vessel for the grandness of the heavens and a haven for microbial research, a practice referenced in the bathroom’s amoebic form. “It’s a place for both the telescope and the microscope,” he tells me. Then, he speaks the opening lines of William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence,” a poem he committed to memory in his youth, and one that returned to him decades later in these woods north of Toronto: “To see the world in a grain of sand / And heaven in a wild flower, / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour.” His recitation is pitch-perfect.

Outside Toronto, the Koffler Scientific Reserve Finds True North

A dorm and learning commons, Montgomery Sisam’s design is a surprisingly intimate marriage of building science and agrarian vernacular.