Toronto is often described as a city of neighbourhoods. The most multicultural city in North America is home to 158 distinct “villages,” “littles,” and “towns,” each reflecting the cuisine, cultural traditions, and civic institutions of its surrounding residents, and each self-identifying through a clustering of businesses, banks, bars, grocers and more that punctuate Toronto’s otherwise monotonous grid of avenues.

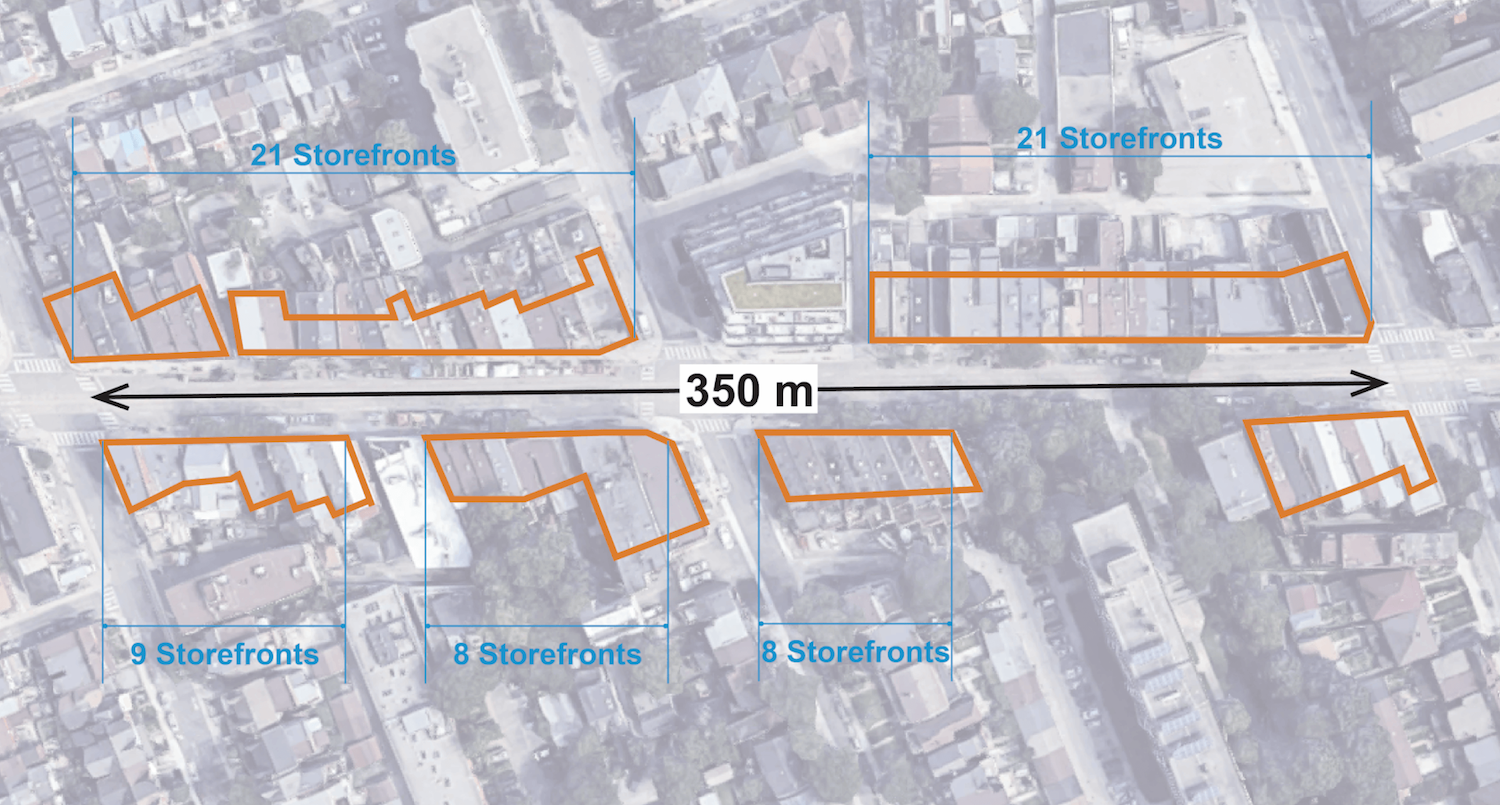

Dundas Street is a staccato of this phenomenon. Traveling west from Yonge, the journey transverses Little Japan, Chinatown, Little Portugal, and Brockton Village, and all the way up through Little Malta and the Junction. While the businesses and communities are diverse and eclectic, the buildings that house them are mostly generic turn-of-the-century structures with commercial uses at grade and one or two storeys of apartments above. Coupled with Toronto’s urban fabric of long and thin Victorian lots, the relatively narrow frontages of these buildings have allowed for tightly packed businesses to establish themselves along Dundas — making rent relatively affordable for upstarts and providing an array of options for surrounding residents in the process. The abundance of affordable commercial spaces on Dundas (and other commercial streets) is central to what has allowed Toronto’s multiple waves of immigrant communities to establish and develop unique local identities.

Unfortunately, these spaces are disappearing all along Dundas (and, increasingly, across the city as a whole). As Toronto adds housing along its avenues and main streets it is also unintentionally decreasing the space available for businesses. This reality is made evident where the ground floor of recent developments stand in stark contrast to surrounding commercial fabric. Consider the stretch of Dundas in Junction between Indian Grove and Heintzman; along the north side’s 50 metres of frontage is a women’s health centre, a Mexican restaurant and grocer, an art hub and art supply store, a cafe and Portuguese restaurant, a drug store, a former laundromat, a vape shop, and a barbecue restaurant. Opposite, only the stocked shelves of an LCBO press up against a tall, flat, glass facade, stretched across the same 50 metres of street frontage. The north side is active and lively while the south is comparatively sterile. The north sidewalk has a rhythm of new storefronts, alcoves, signage, and activity appearing approximately every six metres, while the south is an uninterrupted plane of reflective floor-to-ceiling glass.

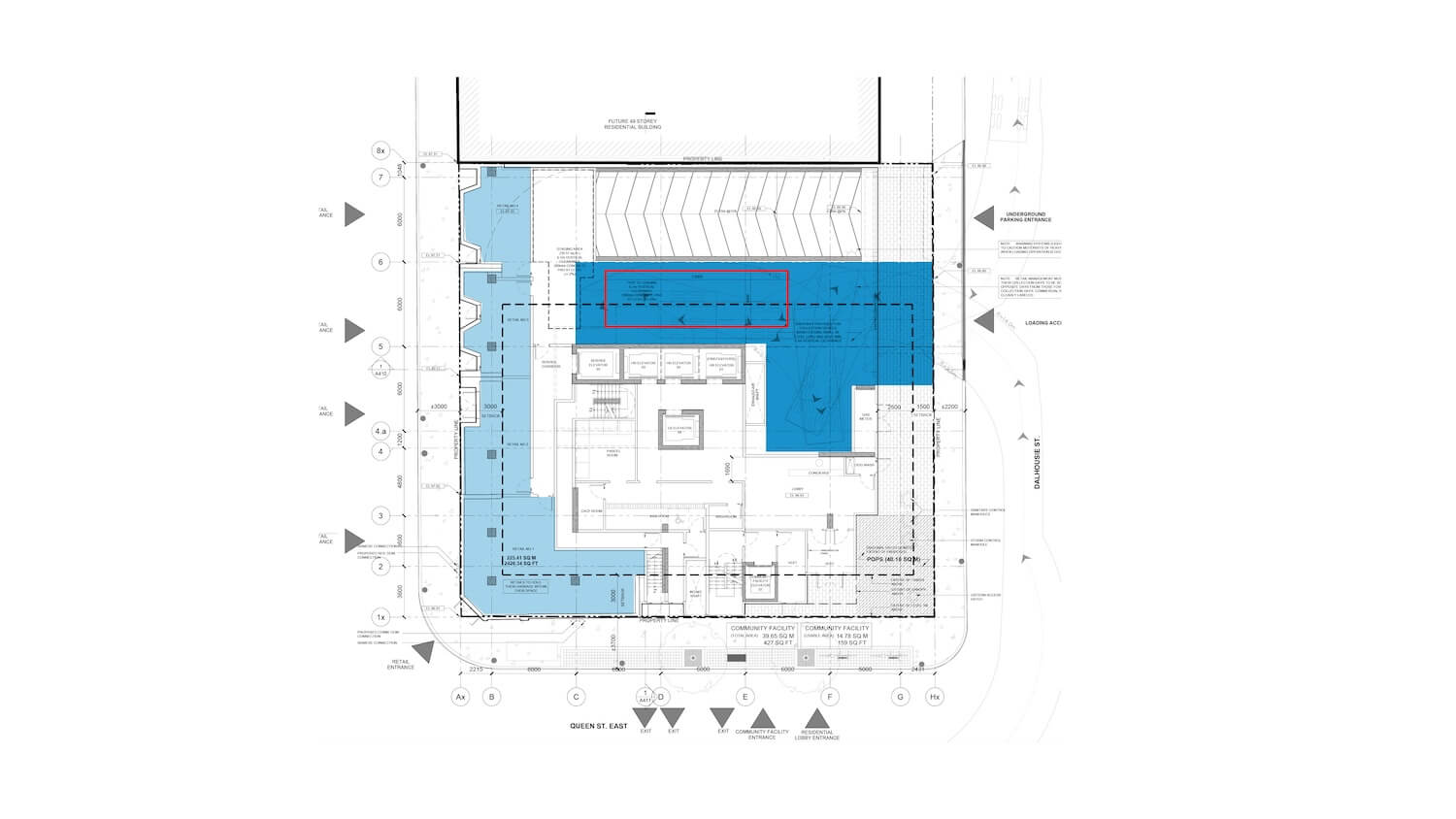

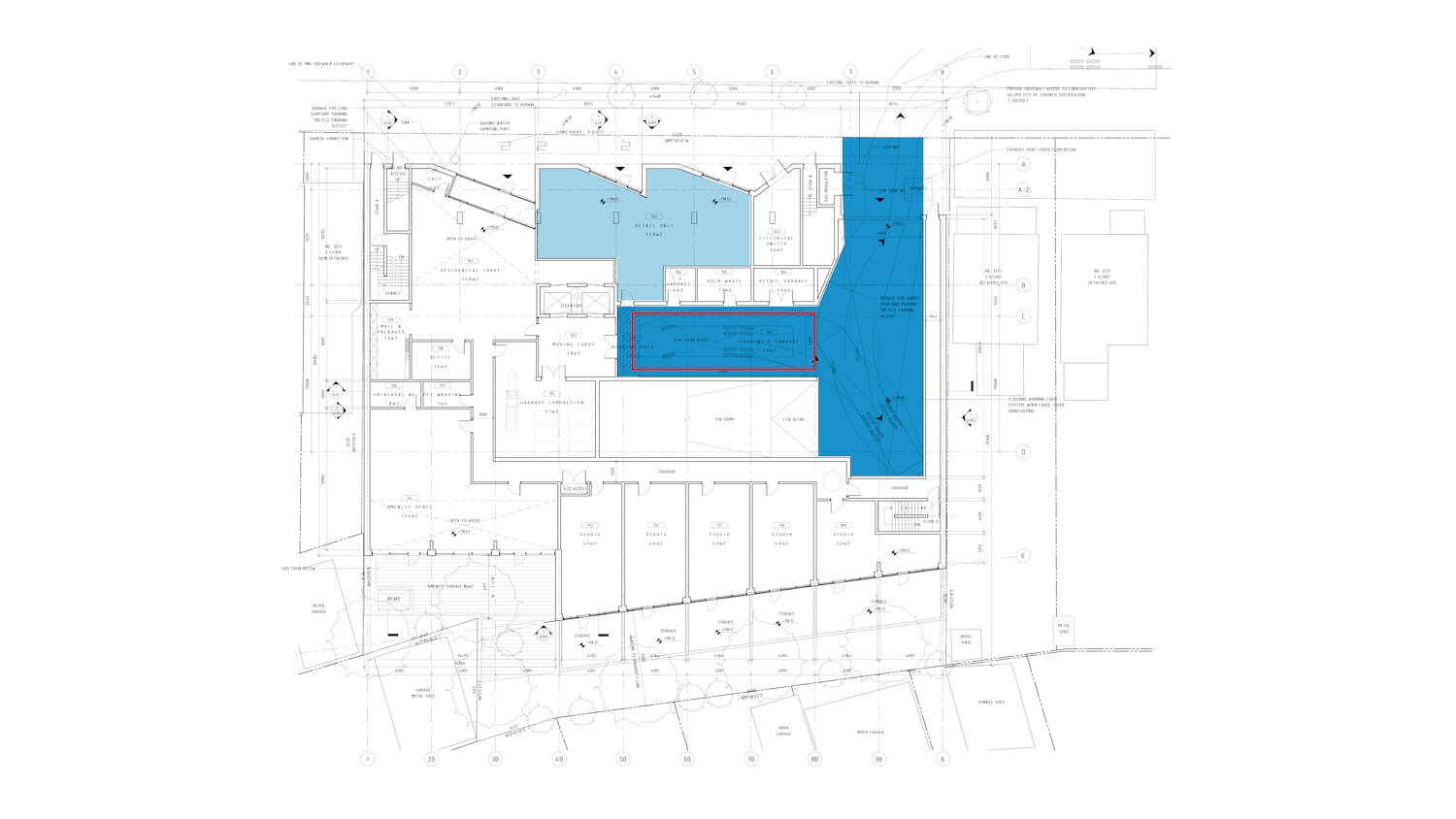

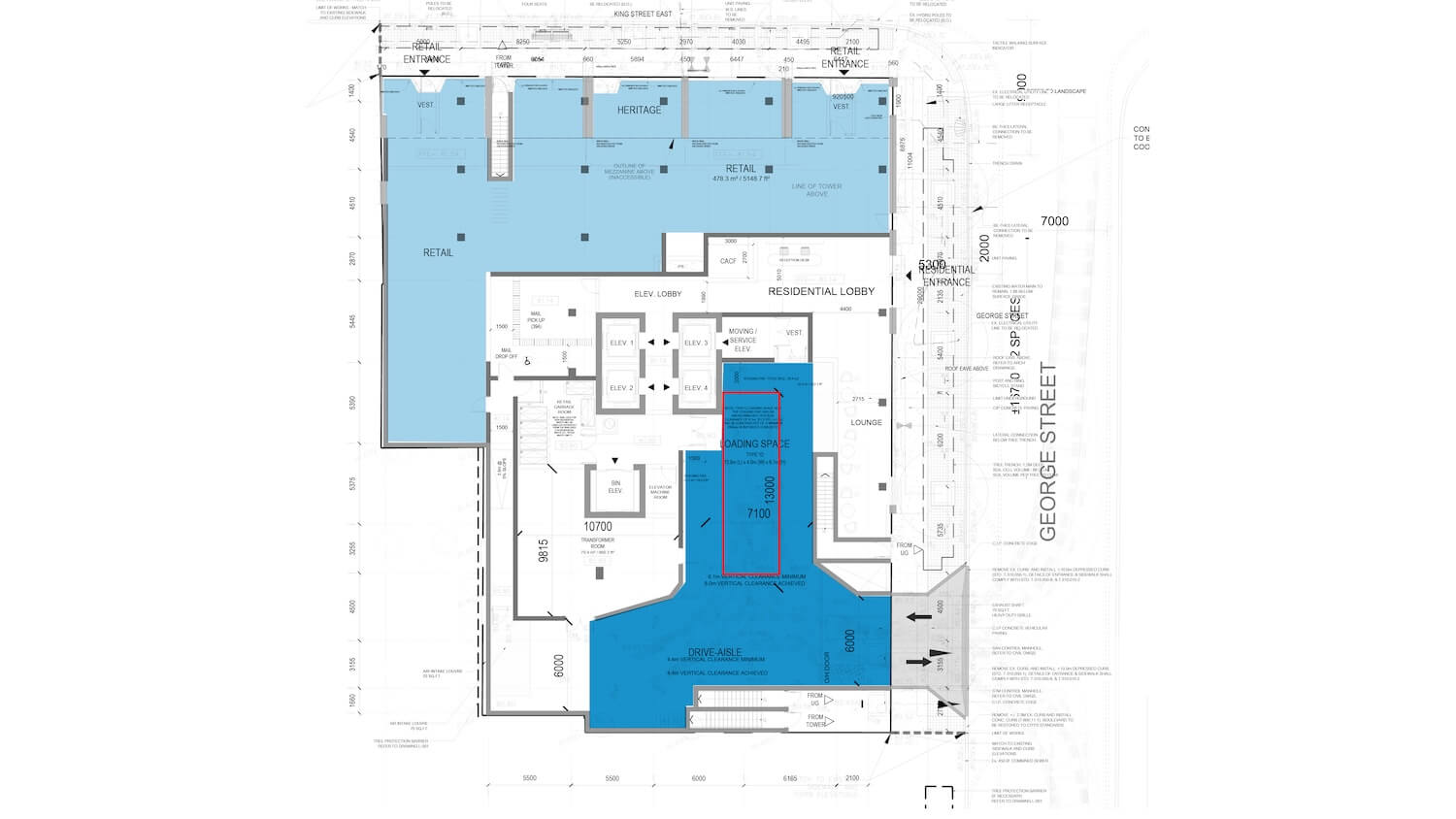

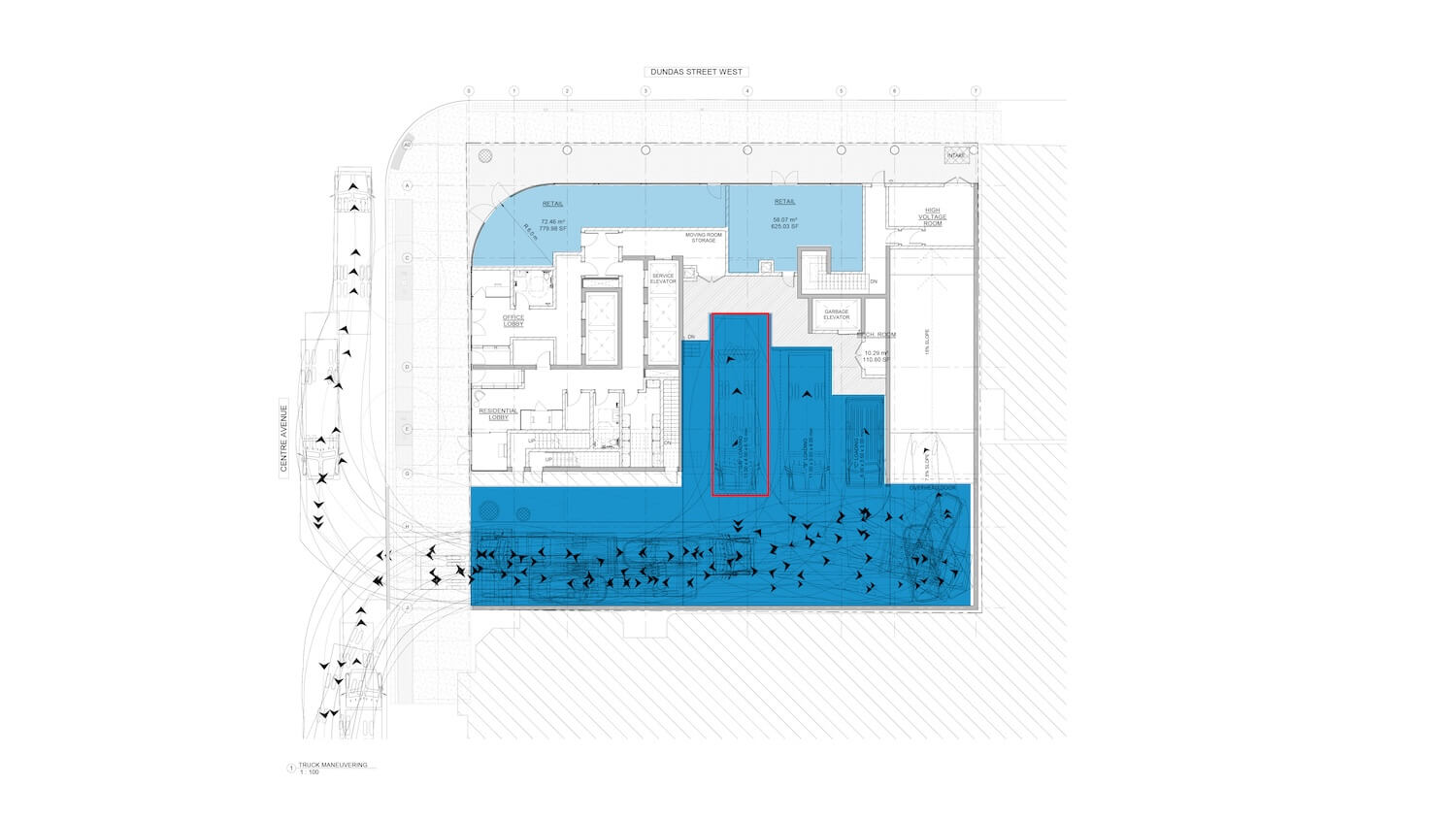

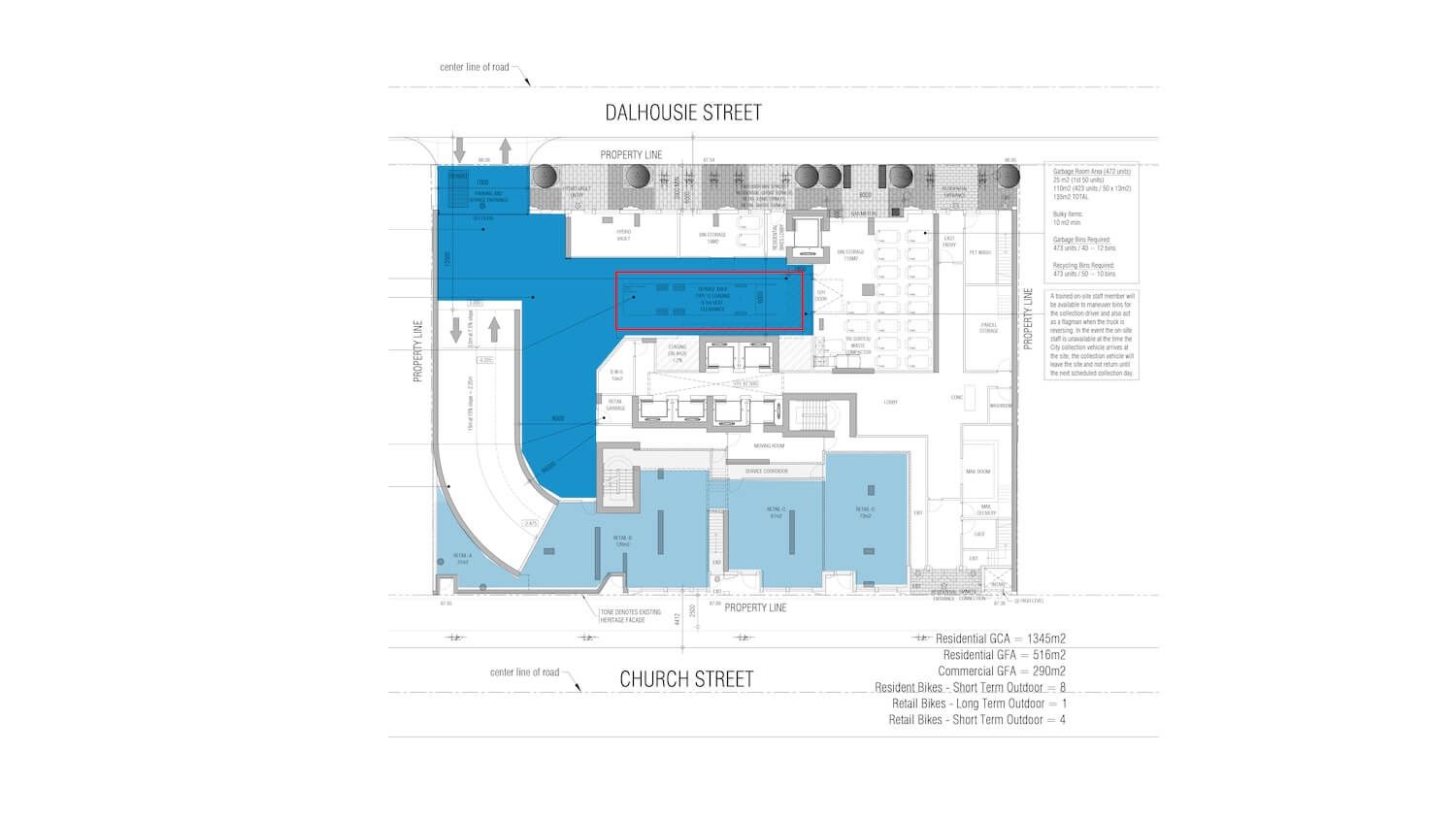

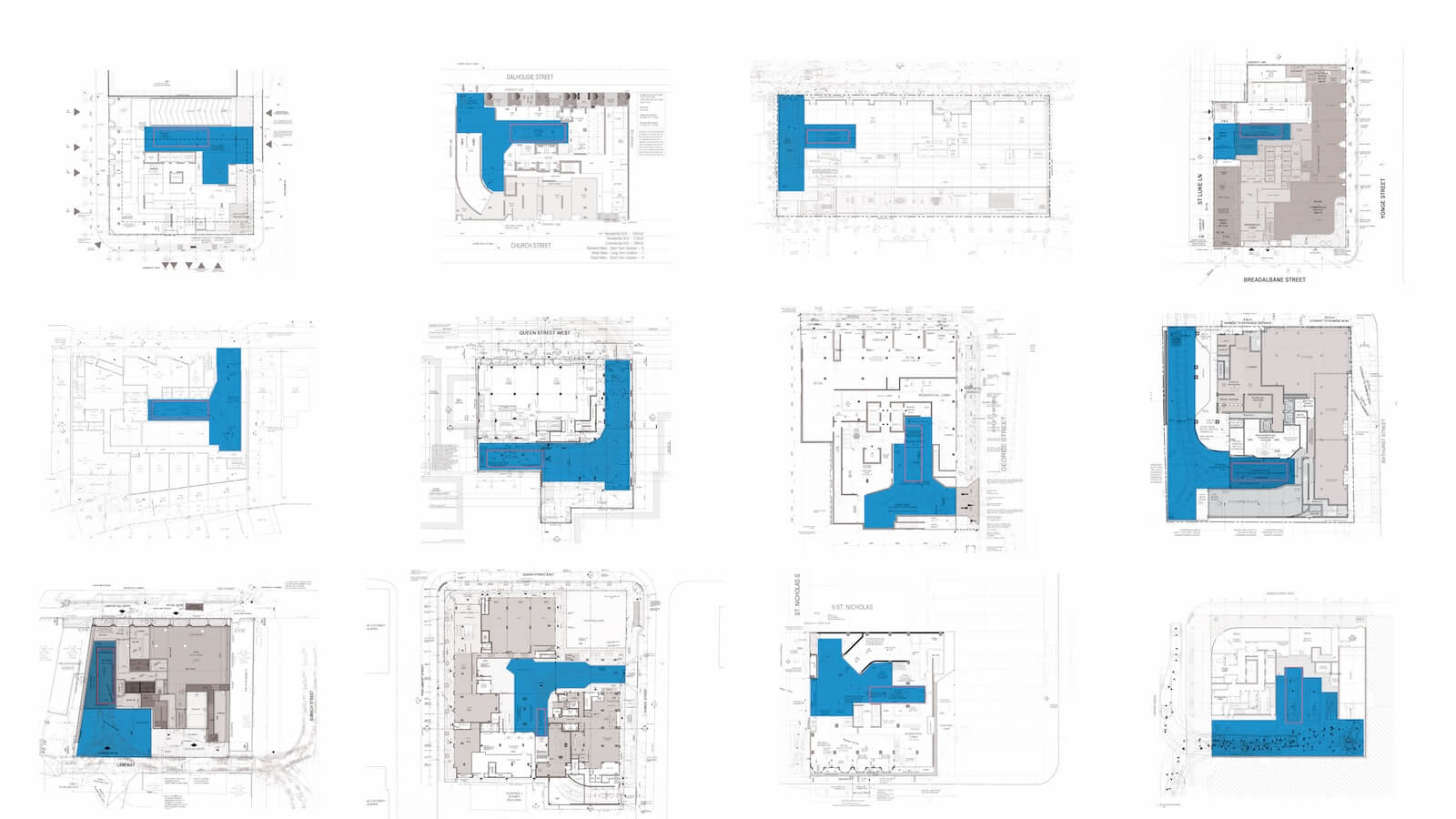

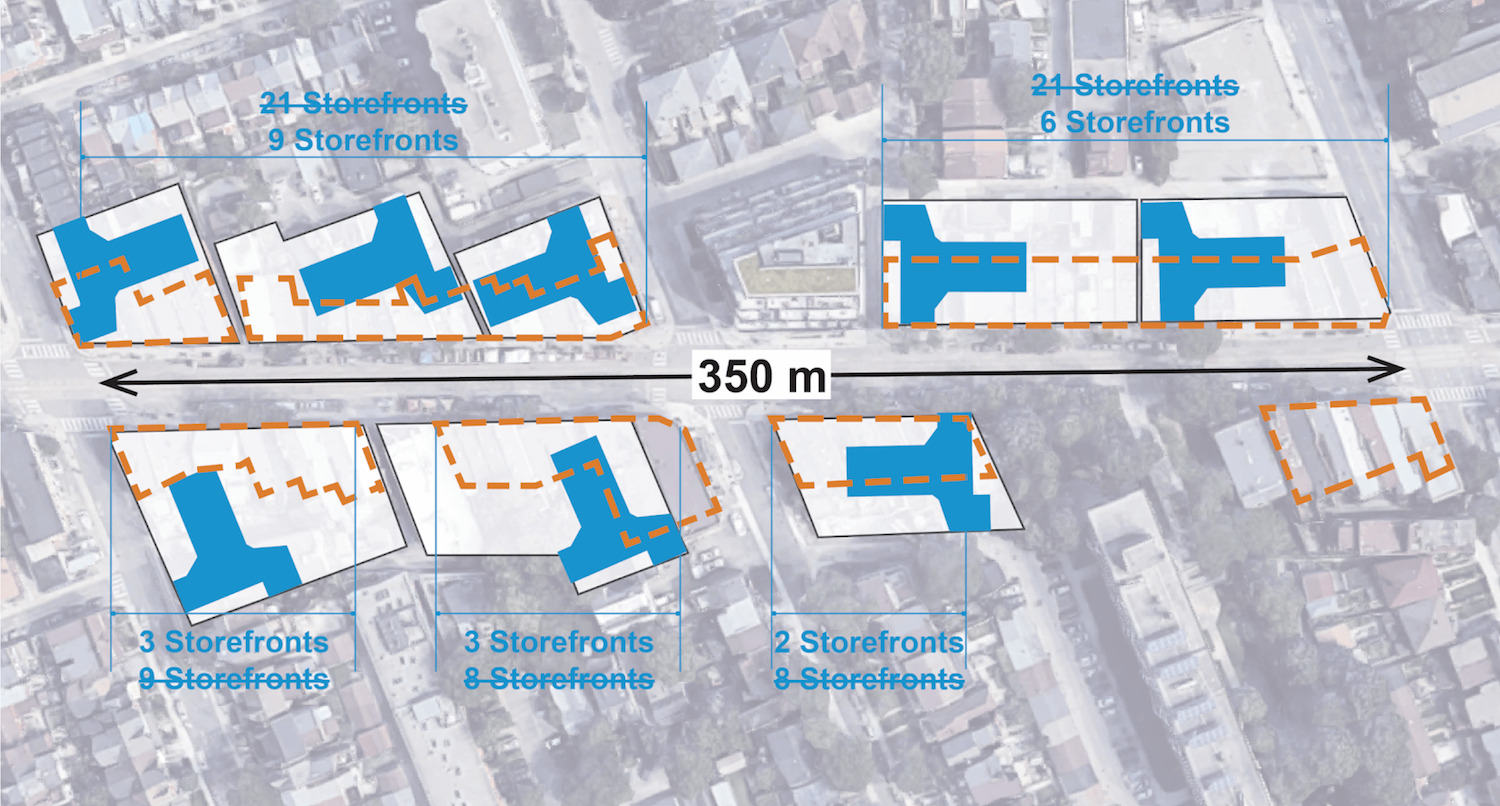

So why are we designing-out spaces conducive to small, independent business? The answer is somewhat surprising; garbage and parking. Toronto parking impact, driven by solid waste handling and on-site requirements, is effectively reducing street-level space for small businesses. One look at the floor plans of the hundreds of projects built or in development across the city reveals how the vitality of our commercial streets is being disembowelled by the three-point-turns of oversized garbage trucks and the turning radii — and parking spaces — that define our car-centric culture.

Many of Toronto’s residents walk their municipal waste to their curb side for the weekly pickup. In a residential building of 30 units or more, however, waste is typically disposed via a chute to a dedicated garbage room on the building’s ground floor. This room is then accessed weekly by one of Toronto’s fleet of large garbage trucks.

In order to accomodate a truck’s large arms to swing a garbage bin up and over its frame, residential buildings require what’s known as a “Type G” loading space, which measures at least 13 metres long, four metres wide and 6.1 metres tall. While the area of the loading space alone is significant, the required turnaround space — allowing trucks to navigate in and out of the building — is often double or even triple its size. Current City of Toronto regulations require this loading space to be designed in order to allow a garbage truck to enter the site, collect the waste, and exit the site without the need to reverse onto a public road — resulting in T- or L-shaped paved areas to accommodate the turns of a wide wheel base. Due to the site constraints and density of these developments, Toronto parking impact and Type G loading is often internalized within the building’s footprint. The outcome? A truck’s manoeuvring effectively consumes the ground floor at the expense of retail space and street-level activity.

Type G also manifests in different ways; where a site has no laneway access, for example, a minimum 6.1-metre-wide driveway might be introduced onto a street facing edge to allow entry. When coupled with a parking ramp to a below grade parking garage the result is that even more of the ground floor prioritized for back-of-house operations, resulting in greater displacement of the commercial uses and a vastly diminished public realm. The net result is a sort of “loading dock-ification” of floor area that interrupts the rhythm of the street and takes up space that could otherwise have active, commercial uses.

From the post-war era onwards Toronto’s growth has been designed around the car. Our street widths, lot sizes, and set-back requirements are all largely a response to our car-dominated culture. With cars comes parking. Our roads, driveways, and parking garages are all sized to house cars. Across most of Canada, constructing a building requires new parking to accommodate its residents or visitors. This was also the case in Toronto until recently; the City of Toronto’s parking requirements stipulating a minimum required number of parking spaces for every residential unit in a new development. And whilst the municipality eventually removed the minimums in 2023 — becoming the first local government in the GTHA to do so — there are still minor minimum requirements for visitor parking and barrier free parking.

Parking also begets more parking. Although only a small number of visitor and barrier-free parking spaces are required, they can still occupy a substantial amount of area. In fact, just three spots, along with a two-way drive aisle, require approximately 100 square metres. This is equivalent to the space needed for a six-metre-wide drive aisle sloped at 15 per cent to access a lower level. Given this, adding a dedicated parking level becomes a logical conclusion — one that can also serve as a selling feature to attract residential buyers. Constructing a ramp and lower level is a significant expense in Toronto, and the requirements for parking have a major impact on extending the underground level across the entire site to better amortize the cost. Additionally, zoning regulations require the parking entrance to be set back at least six metres from the street-facing property line, pushing the ramp further into the site — often creating inefficient, unused space. These seemingly minor requirements can quickly add up — driving the need for full-site excavation. This, in turn, has become a key factor in the widespread demolition of heritage buildings, where only the facades are retained. Preserving the full structure becomes increasingly impractical as these added constraints are imposed on the site.

Finally, while parking ramps are often located near the Type G loading space, the two are typically incompatible, since the loading space requires a flat surface. As a result, the parking ramp must branch off from the turnaround area, extending the vehicular circulation path through the building. This longer path consumes additional floor space, further compromising the building’s street-level layout and its relationship to the urban realm.

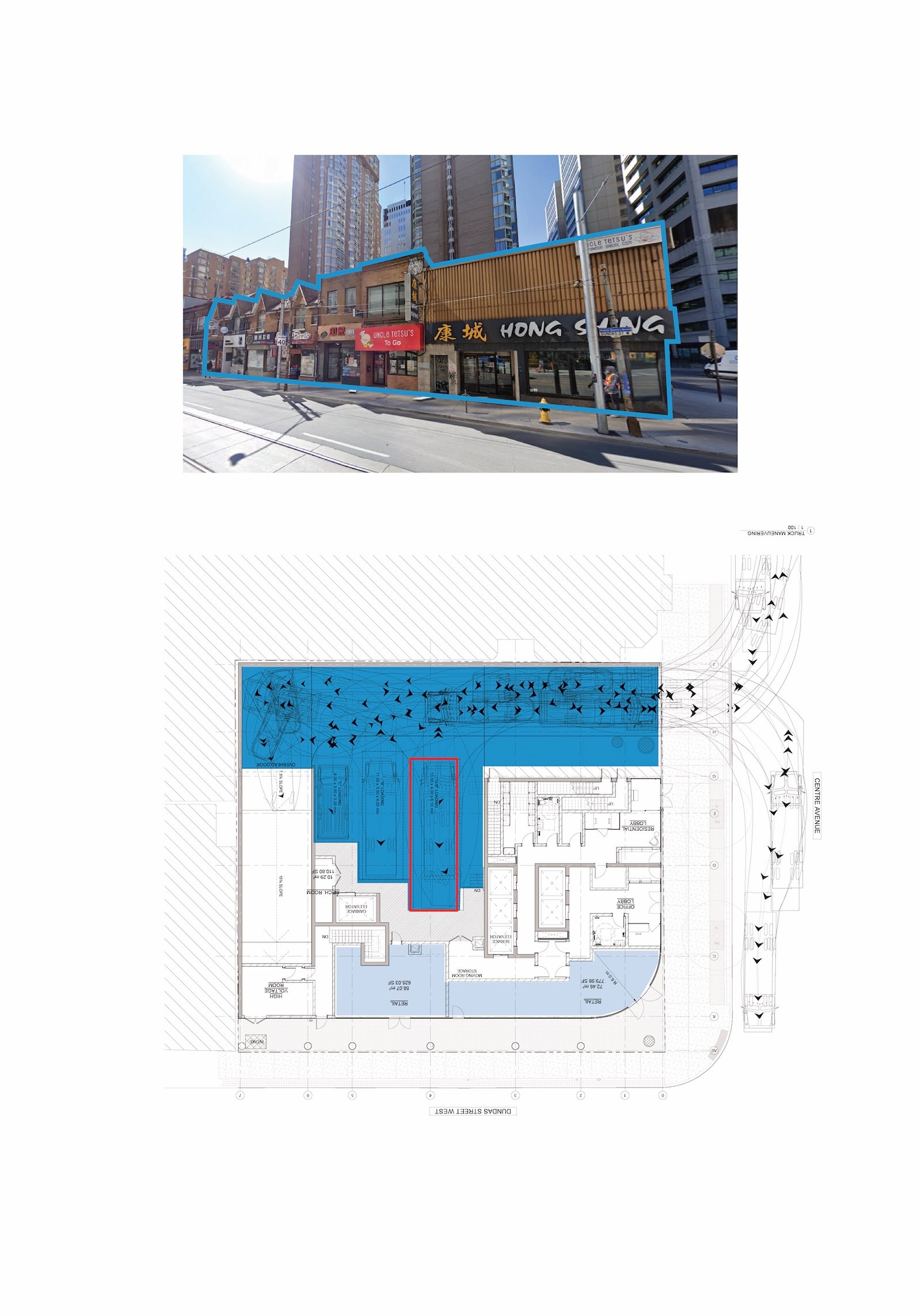

What does all of this add up to? For better or worse, we don’t have to wait to find out what streets like Dundas could become should we continue down this path of development. At the downtown corner of Dundas Street West and Centre Avenue are a series of seven independent asian restaurants in turn-of-the-century buildings — the last remnants of the commercial corridor of the historic neighbourhood known as the Ward surrounded storefronts redeveloped with the street-deadening effects. These restaurants occupy roughly 725 square metres of total retail space and collectively offer significant variety within a walkable distance throughout the day, catalyzing activity on the street, long after surrounding offices close for the night.

This whole block is currently slated for development — the site’s two-storey structures will make way for a 41-storey mixed-use tower containing 135 residential units and new office space. The new tower will require Type G and Type C (a smaller but still substantial footprint) loading and access to underground parking — necessitating over 600 square metres of the ground floor to accommodate their spatial needs. Add to this some 80 square metres of lobbies required to give access to office and residential floors above office and what remains for future restaurateurs is 130 square metres of space to be divided by two new tenants — meaning two of these restaurants would need to get smaller (should they afford to stay), while the other five will be seeking new homes. By providing new homes and places to work, the building dramatically reduces retail space. By prescribing waste and parking behaviours of future occupants, it displaces and diminishes the amenities of the area they’d choose to work and live within.

We have a good sense of the type of retailers these wide, shallow and tall new spaces attract. These spaces are often far more expensive to rent than what was replaced — thus eliminating the potential for small businesses to get a foothold and instead attracting corporate chain tenants that can afford the rent and extensive build outs required. The expansive, glazed frontages of these storefronts are not conducive to the real needs of shelving, storage, or kitchens. Thus, what was once an active cluster of storefronts with views into cafes and restaurants is now a monotonous rhythm of floor-to-ceiling glass covered in branded vinyl to hide functions that would otherwise occupy back-of-house space.

What about potential solutions? Fostering a more vibrant, welcoming and pedestrian-friendly public realm necessitates both a focused reconsideration of vehicular policy as well as a broader cultural reckoning with the city’s evolution. For starters, the erosion of Toronto’s fine-grained, eclectic retail character ought to challenge the practice — intentional or not — of channelling density onto commercial corridors at the expense of the residential neighbourhoods that surround them.

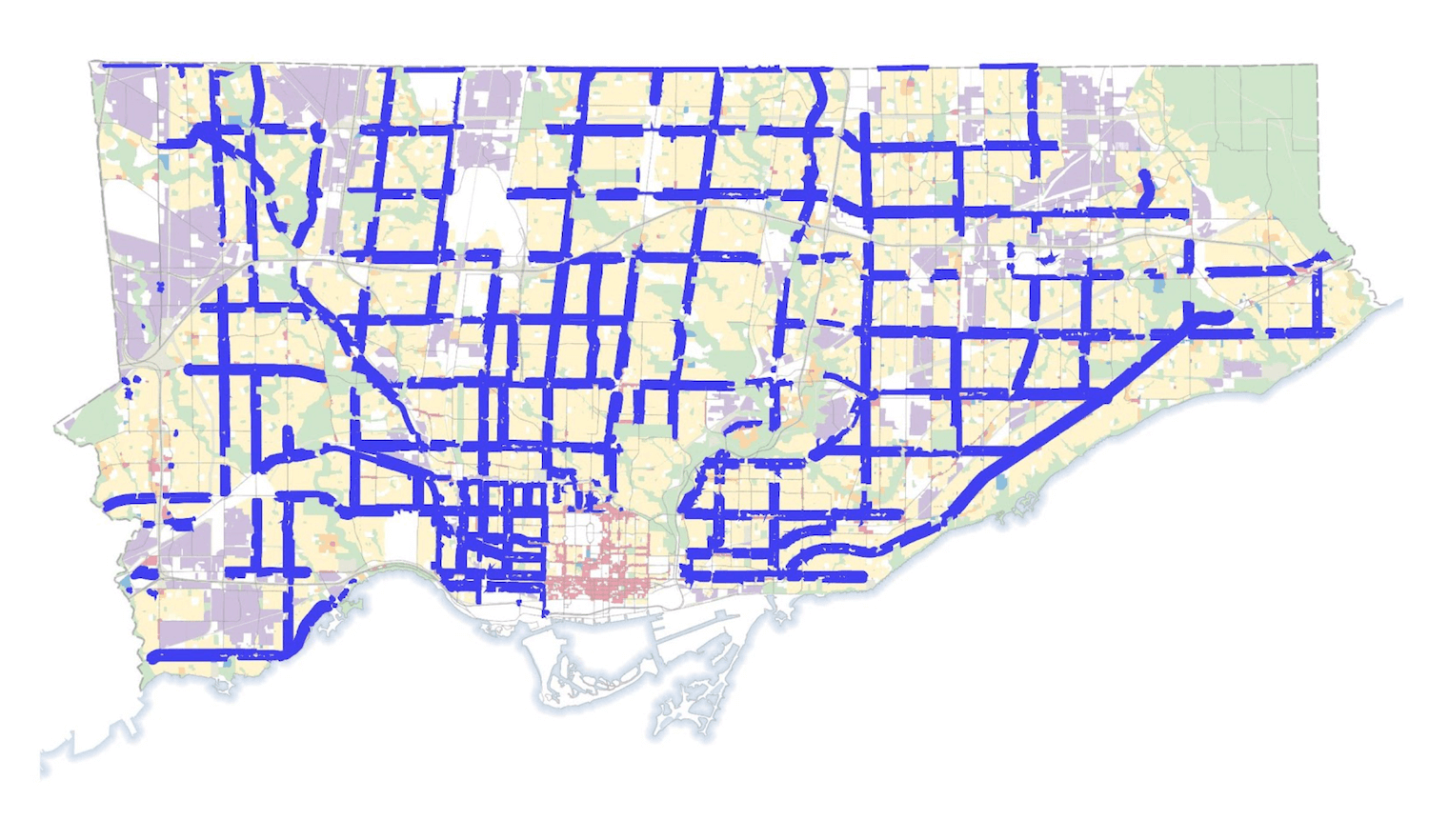

While Toronto’s many “main streets” are among the most iconic and recognizable parts of the metropolis, they represent only a small fraction of the city’s overall footprint — occupying somewhere around six per cent of its geographic area. By contrast, the majority of municipal land area remains occupied by the residential “yellow belt” zone that historically restricted new buildings to single-family homes. Over the last decade, the municipality has made gradual yet halting progress to introduce gentle density to single-family neighbourhoods, many of which have been declining in population amidst a worsening housing crisis.

In 2018 and 2022 respectively, new laneway house and garden suite regulations introduced incremental changes to neighbourhood planning policy, while 2023’s Expanding Housing Options in Neighbourhoods (EHON) program scaled up the still-modest ambitions by allowing multiplexes within neighbourhoods — as well apartment buildings on major streets and as-of-right mid-rises on the avenues. These are small steps in the right direction. Yet, meaningful progress has been frustratingly slow. A recent push to legalize six-unit apartment buildings across Toronto — taking advantage of a new CMHC housing design catalogue — was watered down to just nine of the city’s 25 municipal wards, restricting progress. While politically expedient, such decisions must be understood within the context of a larger land use paradigm that channels more growth onto commercial corridors.

More acutely, the regulations governing new mid- and high-rise buildings ought to be thoroughly reconsidered. First, exemptions for the loading space requirement could easily be extended well beyond 30 residential units, allowing larger buildings to be constructed in a more efficient, street-friendly manner. Visitor parking requirements could also be fully eliminated, while maintaining strict yet spatially efficient accessibility standards.

Garbage policies should also be re-evaluated in light of its urban impacts. To wit, it’s worth rethinking our dependance on massive North American trucks. In lieu of a weekly collection in a hulking vehicle, there could be more frequent pickups with smaller trucks, borrowing from paradigms long established by cities across the world. What’s more, storage systems that are removable via the curb side would alleviate the need to enter the site, freeing up more of the building’s footprint for deep, narrow retail units. It doesn’t entail experimentation or wild risk-taking — all of these are well-established global precedents. Thinking ahead, self-driving garbage bins which stage themselves would limit the on site requirements for garbage.

To be sure, there are viable strategies to reduce or eliminate the need to dedicate large areas of prime urban sites to garbage-related uses and parking. Ultimately, the loss of Toronto’s architectural heritage and fine-grained urban retail — not to mention the eclectic, multi-cultural vitality it nourishes — isn’t an inevitable outcome of a bigger and denser city. But giving up so much valuable space to parking and waste constitutes a type of waste in itself.

Mitchell May is an architect, heritage consultant, and certified passive house designer. An associate at Giaimo, Mitchell is also a member of the City of Toronto’s Toronto Preservation Board, as well as the CAHP Education and Professional Development Committee.

Kelly Alvarez Doran is a founder of Ha/f Climate Design, an adjunct professor at the University of Toronto, a Senior Fellow of Architecture 2030, a founding member of the Bio-based Materials Collective, a winner of the Canada Council’s Prix de Rome for Emerging Practitioners, and a member of the RAIC’s Committee on Regenerative Environments.

Parking, Garbage and the Decline of Toronto’s Small Businesses

Kelly Alvarez Doran and Mitchell May examine how loading regulations and car-centric design standards create lacklustre retail in new buildings.