What might a building designed for A.I. innovation look like? Ask ChatGPT, and you might expect the online software to conjure complex algorithmic forms, holographic displays or even a dynamic smart facade. Instead, its response is surprisingly practical: “A building designed for A.I. innovation would reflect the technology’s emphasis on adaptability, efficiency and cutting-edge research,” it tells me. In dreaming up the Schwartz Reisman Innovation Campus (SRIC), a new tech incubator at the University of Toronto whose tenants include the Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence (led by Nobel laureate Geoffrey Hinton), New York firm Weiss/Manfredi didn’t rely on A.I. for design inspiration. And yet, when I tour the building on a rainy morning in March, it’s clear that the final product delivered on these imperatives — and much more. When I step off the streetcar, I’m struck by how faithfully it resembles the original renderings, the concrete structure massive yet remarkably porous.

Like much of the firm’s portfolio — which hews toward contextually attuned academic and cultural buildings — the project started with its site. The SRIC sits on a prime piece of real estate: Located at the intersection of College Street and University Avenue, it is nestled between the MaRS Discovery District — North America’s largest urban innovation hub — and Queen’s Park, the home of Ontario’s provincial legislative buildings. That being so, the new building was designed to carefully negotiate a connection between the campus and the city at large. “You couldn’t think of a more dramatic mix,” says partner Michael Manfredi. “The university recognized that this wasn’t on the historic campus, so it had to be a forward-looking building. And because it was such an incredible hinge site, it also had to have a public dimension.” Additionally, its proximity to Queen’s Park drove some important zoning considerations: There were to be no shadows on the Park. To that end, the architects devised a canted facade that lends the structure its distinctive tapered geometry. “It goes beyond being just an academic building. It really becomes an urban citizen,” adds Marion Weiss, who co-founded the firm with Manfredi.

The project isn’t without controversy, however — the Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, an important piece of the city’s scientific history, was demolished to make way for the SRIC (its legacy lives on through the Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, which opened in 2005). But with its predominantly precast concrete palette, the building still aims to pay homage to Toronto’s ’50s and ’60s heritage. Though the facade looks simple at first glance, the devil is in the details. “The panels look identical, but there are slight parametric shifts as you move up the building, in service of trying to get an economy of scale on the windows, which are all the same size,” explains Wes Wilson, a principal at Toronto’s Teeple Architects, the project’s architect of record. “It took a month of research and development to design the family in Revit.” Carved into the pre-cast concrete envelope, a graphic glazed cut-out shaped like an upside-down L hints at the communal spaces above.

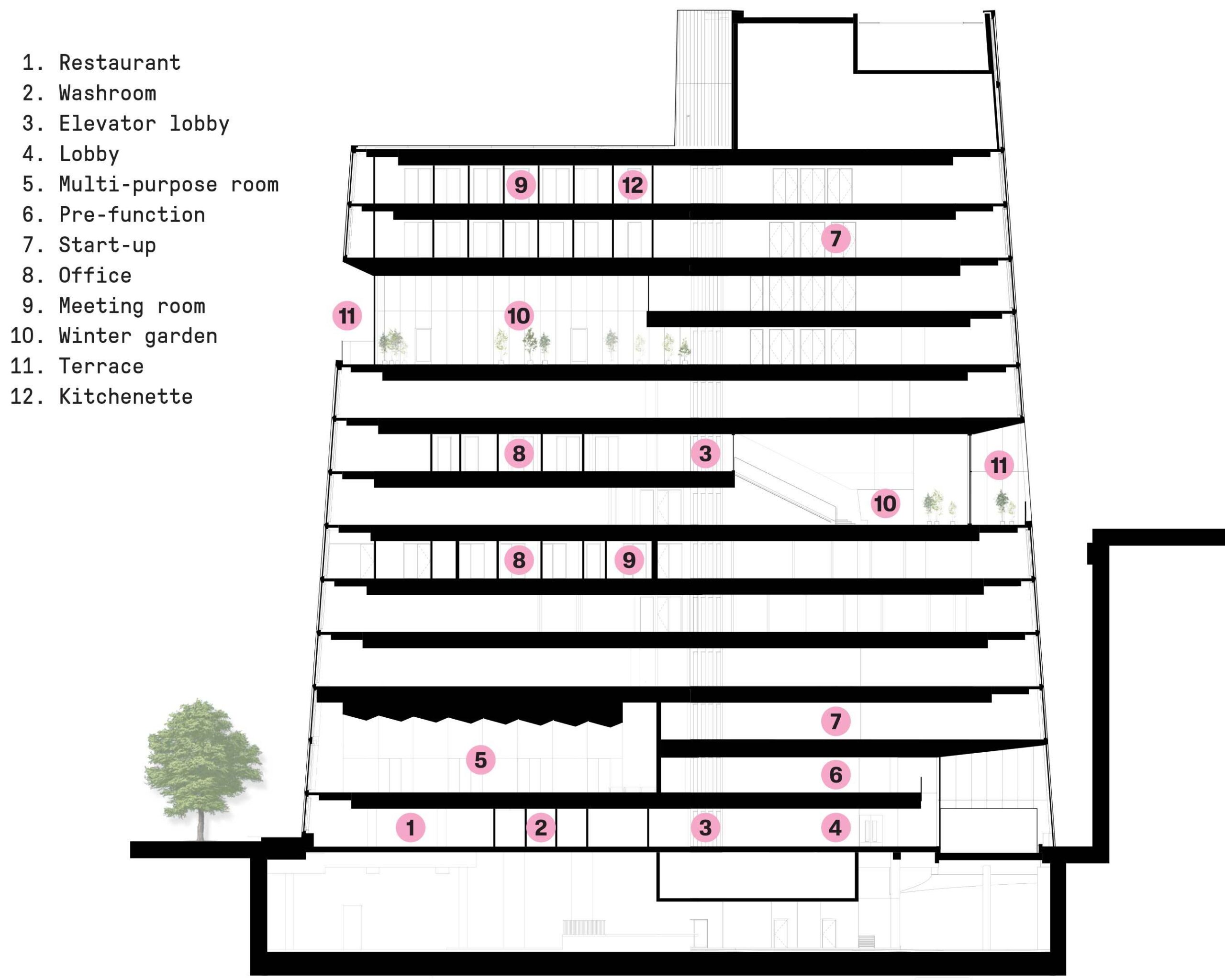

At street level, this ethos of city- and community-building is especially apparent where the curtain wall facade and the landscape (by Toronto’s DTAH) welcomes the public inside — a marked change from the mostly opaque street fronts along the College Street corridor. The generous lobby leads up to a mezzanine level, complete with meeting and collaboration spaces, plus a warm, wood-clad auditorium that feels more like a cultural space than a tech hub. In the latter, light reflects off the zigzagging wooden ceiling, which conceals a complex structural system of concrete coffin beams — and projectors that drop down when hosting conferences and other events.

But how do you introduce a sense of intimacy and connectedness in a multi-level building? “At the very beginning, we said that if the goal here is collaboration and cross-pollination, it’s not going to happen independently within the labs. It’s going to happen in-between, and those between spaces need to benefit from as much generosity as possible,” Weiss explains. The circulation, then, becomes part of the public realm: The elevator cores are expansive, giving people space to stop and talk as they wait, while the fire stair, located on the University Avenue frontage, is filled with natural light, encouraging tenants to take the stairs — and hopefully make connections along the way. Throughout, the architects leveraged double-height volumes to create views between floors, including two “winter gardens” strategically placed to engage with Queen’s Park. While they are flexible enough to host anything from lectures to weddings, on most days they serve as informal social zones with banquette seating, café tables and lounge vignettes.

For the lab and office floors, the architects conceived minimal, loft-like spaces subdivided into units of various sizes, allowing private areas for focused work (especially important in the tech sector, where tenants may be working on distinct IP). Businesses can sign short- or long-term leases, which allow start-ups to scale from a one-person operation to eventually take over an entire floor, if needed. Given the rotating nature of the occupants, the suites were designed to be easily adaptable. “Innovation is changing at such a rapid rate that we really shouldn’t be designing something so specific that by the time it’s built, it becomes outmoded. It’s nothing radical, but we looked at the simplest loft spaces with lots of power, flexibility and generous windows,” Manfredi explains. “We wanted to give them flexibility now and into the future, and the specificity would arrive only when we were looking at the collaboration spaces and all the connective tissue.” The simplicity of the design is ultimately what makes it so versatile. “We’ve discovered that ‘tech-driven,’ in many ways, is just notational as a kind of program, because, most importantly, we always think about buildings as having an enduring identity and capability over time,” Weiss continues.

This malleability is especially critical given how the site will continue to evolve in the years to come. Though the timeline remains unclear, the next phase of the project will see a second, taller tower built to the east of the SRIC, this time focused on regenerative medicine research. “One of the challenges when you do a phased building is that you never quite know when phase two is going to occur,” says Manfredi. “We wanted to make sure that the first one felt complete enough that if we’re 10 years out, it doesn’t feel like this building’s missing an arm or looks half-finished. Hopefully, when phase two goes ahead, you’ll feel that it’s sharing the same DNA and has the same ethical position about its relationship to the city.”

A Toronto Tech Campus Champions Human Connection

Designed by Weiss/Manfredi, the home of A.I. at the University of Toronto embraces a community-oriented ethos, inside and out.