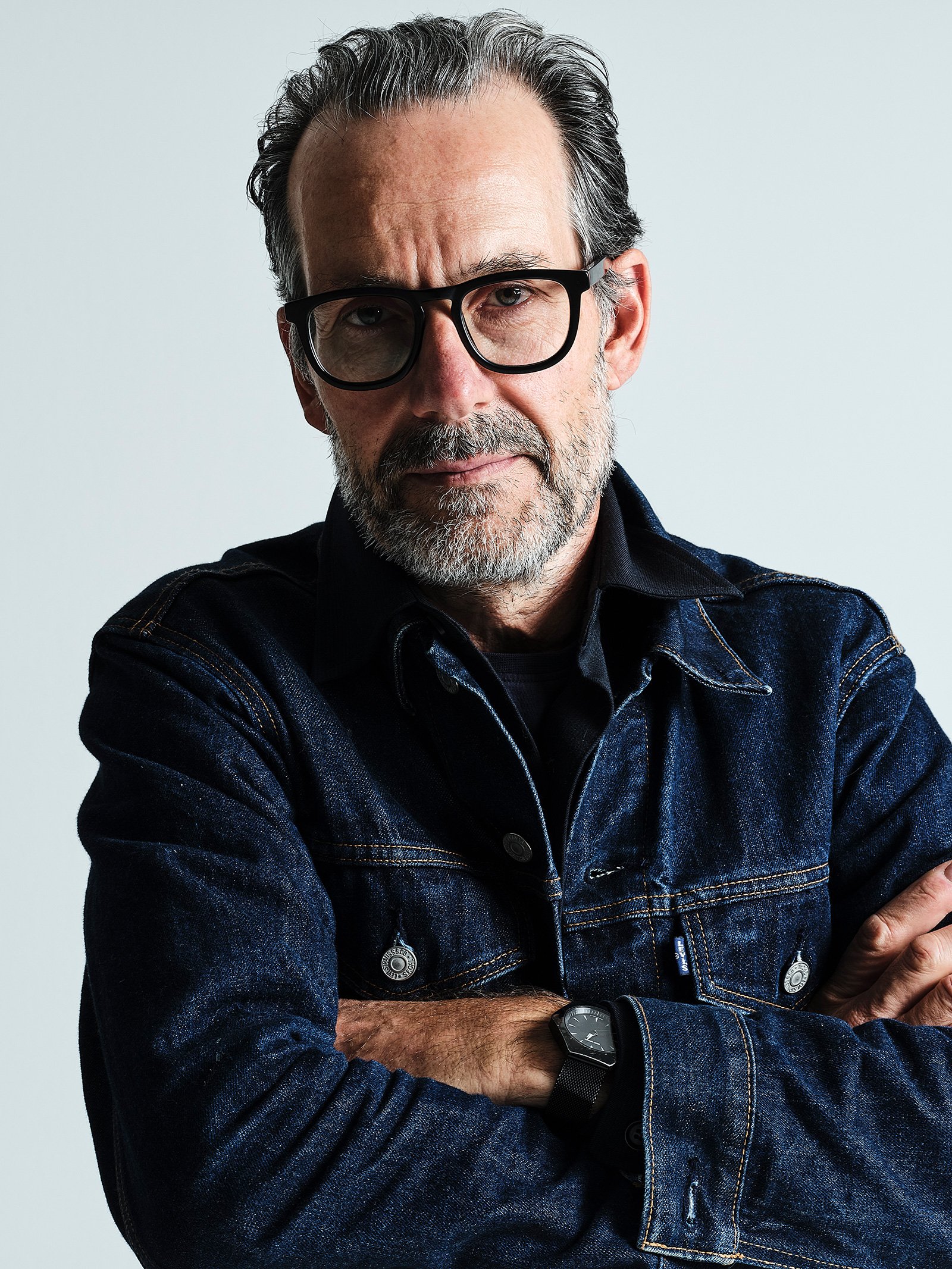

As soon as Konstantin Grcic joins our Zoom call, it is clear why he was the perfect person to co-curate White Out. The Future of Winter Sports, a new exhibition at the Triennale Milano that explores design’s role in the evolution of skiing, skating and other cold-weather recreational pursuits. While his co-curator, Marco Sammicheli (who leads the Triennale’s design, fashion and crafts sector, and is also the director of the Museo del Design Italiano) joins from his office wearing a crisp navy sweater, Grcic logs on dressed in a cozy pile fleece vest, reporting for duty from a woodsy chalet that he reveals to be located “not so far from Cortina.” But rather than sitting in the spectator stands for the 2026 Olympics, he is on an alpine holiday with his family.

As anyone who has ever packed for a ski trip can attest, winter sports require a massive amount of gear. A large part of that is thanks to the extreme conditions that one must endure while partaking in said sports. Mind you, on many of today’s slopes, blizzards and sub-zero temperatures are not as common as they used to be. This month, the Olympics announced that they are even considering shifting future Winter Games from February to January to reflect the shifting nature of the season. As climate change continues, ski resorts increasingly depend on artificial snow to stretch out the season — spurring the development of even more equipment.

Somebody needs to design all of this advanced gadgetry — and these are exactly the creatives who Grcic and Sammicheli are here to celebrate in White Out. Collecting some 200 objects, the exhibition charts major milestones in ski and snowboard design, as well as highlighting the infrastructural innovations that will continue to make these sports possible. (The title of the exhibition is a play on the uncertainty of winter sports during the time of climate change, and the path forward that designers will ultimately help carve.) Along the way, White Out also showcases memorable architecture projects from the likes of Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret. Best of all, while skiing can require a big investment, the exhibition (on view until March 15) offers free admission.

Below, Grcic (KG) and Sammicheli (MS) share an extended chairlift ride’s worth of insights into the planning and design of the exhibition.

To start things off, what sort of personal relationship do each of you have to winter sports? Konstantin, based on your chalet Zoom backdrop, you seem like you’re no stranger to the slopes.

- KG:

I love skiing and grew up going with my family. I spent many years in the south of Germany, which is just an hour away from all the good ski places. In my best years, I’d go 25 times. This year, I’m probably skiing about 15 days, which is still a lot for someone based in Berlin where there are no mountains. Berlin schools have something that they call ski vacation, which is this week. I’m not sure how many Berliners are actually going to ski, but we are.

Today it’s been snowing all day, and it was a true white out day with no vision. The slopes were empty and it felt like skiing back when I was a kid. I have all these memories of bad weather. My kids have grown up thinking that skiing is always sunshine and blue skies — but today was a real ski day.

- MS:

I am similar. I was born by the sea, and it was mandatory that we had to ski for Christmas time and Easter. I remember my father with his Golf GTI installing skis on the roof of the car, and then me and my brother sitting in the back driving to Madonna di Campiglio. As a kid, there was this Italian skier who, for us, was our hero — Alberto Tomba. Watching TV when he was competing for the Ski World Cup was a big event. But to mark a sort of difference between the ability of me and Konstantin, I don’t own a pair of skis — I rent. That tells you a lot about someone’s passion when they own their own equipment.

That brings us to equipment. Performance and safety are two big focuses of the exhibition. Tell me about what you learned about the advances made over the years in both areas, and how some of the objects on display maintain a balance between them. Skiing during my childhood, nobody wore helmets, but now when you go to the slopes, the vast majority of people — thankfully — are.

- KG:

Yes — in fact, helmets have become mandatory in Italy. Performance and safety have definitely been the key drivers for design development and also for how skiing has generally evolved and developed over the years. Performance can mean going faster, but it can also mean comfort and ease. And I think we’ve mainly seen improvements there. Fast skis have always been here. But it’s amazing how now, you hardly see any bad skiers on the slopes — and a lot of that is due to the improvement of skis.

There was a time in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s when snowboarding became real competition to alpine skiing — it was cooler, and it felt like alpine skiing was becoming boring. It’s amazing how skiing then reinvented itself to become fun again, and also very inclusive to different skill levels. Now, people don’t need to spend five, six or seven years practicing just in order to make it down a slope. There’s been incredible creativity in the market. Carving skis, skis with lighter materials, shorter lengths of skis, and more optimized bindings and shoes — all of those have been big shifts. And they’re driven by this being a money-making industry that calls on design to find solutions, and also on the athletes themselves placing more demands on designers. It could have all failed terribly, but alpine skiing in the past two or three decades represents an incredible success story.

- MS:

Let me just add that we took the relationship between these two aspects — performance and safety — very seriously in that we did not want to present this polarization with performance on one end and safety on the other. Usually, there might be this idea that “If I have to be safe, I won’t experience the braveness.” But thanks to industry progress, you can now have great fun with a very high standard of safety.

In the exhibition, there are a series of “before and after” walls where you see alpine skis, ski jumping skis and cross-country skis as they were in the ’80s, and as they are now. You can see the progress in terms of safety and general standards. But this was also a subject that has been addressed at all different scales. It’s not just about skis or equipment, it’s also about infrastructure, which is also covered in the exhibition.

That’s a good point. What role has design played in safe ski hill design?

- KG:

Thirty or 40 years ago, there were maybe just some sticks on the side of the slope to give some form of orientation during these foggy white-out moments. Now, there are nets and crash barriers everywhere. Whenever I’m skiing, I love looking at all this equipment and the different materials used for it, because it looks cool. Design is this guide to find rational, efficient and consequently I’d argue, beautiful solutions — it’s a key element in the whole experience.

What was the research like for the exhibition — who were some memorable people you spoke to and things you discovered during that process?

- MS:

The exhibition mirrors the wide spectrum of disciplines represented in the Triennale — we’ve been careful to include fashion, infrastructure, photography, and so on. And every single person we met — academics, entrepreneurs, athletes, trainers, workers — was filled with passion and had such extreme vertical knowledge. We’d meet someone who knew everything about how a certain material performs in certain conditions. This is an exhibition that gives voice to these aspects of design that are usually very silent. Reading the wall captions, you learn all these new things that are secretly fundamental to your experience when you are in the snow.

- KG:

I should mention one trip that Marco, myself and my assistant, Nathalie Opris, did together. A lot of the state-of-the-art innovation — in terms of equipment, but also in terms of infrastructure like snow cannons and ski lifts — happens in the alpine region of northern Italy. We went to visit companies there and have conversations with their researchers and technicians. Dainese is one example — it is one of the leading companies in protective gear for skiing, and it was established long ago by someone who had a personal passion for it.

Beyond that, we also spoke with an interesting professor at the University of Innsbruck in Austria, who does research specifically about the evolution of winter and summer tourism in the alpine regions in light of climate change. He looks at concrete data to forecast what is going to happen, and from that research we produced one interesting wall in the exhibition. It has data visualizations designed by the Milanese graphic design studio Propp showing three consequences of climate change to winter sports. One is that resorts will move up to higher altitudes. Another is that resorts will need a lot more water in order to produce more artificial snow, which is already something that winter sports can’t exist without. And the third is that the winter sports season will shrink from roughly 100 days per season down to about a quarter of that.

Speaking of snowmaking: How do you feel about the relationship between winter sports, nature and technology? Should people be able to ski inside in Dubai?

- KG:

I have actually been to Dubai, and I couldn’t resist going skiing there. You step into this mall from a 30-degree, super hot environment, and then suddenly you are in a below-zero environment on this inclined surface. I have to say, I had fun, and all the people I saw around me were having fun.

There’s a famous British skier right now, Dave Ryding, who is one of the top skiers in slalom, and all of his career he’s been practicing indoors on dry slopes. It’s true that winter sports are about being outside in nature to a certain degree, but they all need the support system of quite an incredible engine running with water, pipes, turbines and all those things. I’m passionate about skiing, so I find arguments why these things are okay.

Last week, Marco and I hosted an internal seminar, and there was an architect who had actually been a professional ice hockey player and part of the national Italian team at the Sarajevo Olympic Games. He told us that indoor ice skating in an enclosed environment was actually invented in Milan. Of course, it’s beautiful to ice skate on lakes, but we don’t think twice about ice rinks where the ice is artificially produced and kept up by these engines that use a lot of energy. And in contrast to downhill skiing, which is quite an expensive sport, ice skating is a super beautiful, democratic sport. I go ice skating with my kids in Berlin, and that’s one place where everyone can skate for a couple of Euros and have fun. It gives so much pleasure to a lot of people.

But I do think that, to really argue for year-round winter sports, we have to optimize the system in terms of where the energy comes from and how we can reuse it. There is great potential to manage it more efficiently.

- MS:

At the beginning of planning the exhibition, we had originally thought of ending the show with one of these spectacular examples — Dubai or the ski hill that Bjarke Ingels designed in Copenhagen. Instead, we ended up commissioning an AI-generated movie from Scott Cannon, an American media artist based in Berlin. He worked with existing data and research on how winter sports are already changing due to the climate, so that what we see in the video are things that — like the ski hill in Dubai — look futuristic and spectacular, but are actually already happening.

Of the 200 or so objects on display, is there something that left an especially strong impression on you, or that seems to be really resonating with people?

- KG:

We have some amazing contributions from very specialized companies. There is a two-seater bobsled, for example, used by the German national team and it’s from a company that you can’t really buy from — it produces exclusively for the Olympics and competitions.

- MS:

A lot of the audience relates to the outfits and uniforms. There’s a rotating mannequin with one of Katarina Witt’s ice skating dresses. It’s completely low tech and stands for the incredible talent of an athlete — showing that the main engine for everything she does is her own body.

You also see a 1970s ski boot by Tecnica that looks just like a modern Rick Owens boot. Someone in the 1970s was envisioning something that is aesthetically very current.

To that point — how do innovations or styles developed for winter sports impact our lives beyond the ski hill or skating rink?

- KG:

Equipment for extreme conditions — especially protection against the cold — demands the development of new materials — breathable, lightweight stuff that doesn’t get soaking wet and still looks really good. The fashion industry has picked up on these developments that come from the demands of these extreme conditions. But other times they take stylistic inspiration. One of the most beautiful exhibits in the show is a high heel boot designed by Nicolas Ghesquière for Balenciaga that was clearly inspired by snowboard bindings.

Sportswear merges futuristic technology and mechanics with strong colours and experimental shapes. Sports designs can go much further in their expressions and people will still wear them. In comparison, in furniture and other areas of design, we are so much more conservative. But when it comes to sports equipment, we go with the newest, craziest stuff. That’s a beautiful thing, and it’s why this exhibition is so relevant. Yes, we’re looking at design with a focus on sports, but it’s very clear the effect and influence that this has on other areas and disciplines.

- MS:

There’s a photo in the exhibition from a 1970s snowmobile campaign where the three models are wearing helmets, suits and moon boots, and they look like Power Rangers from a Japanese manga. The fashion world has always been fascinated by the idea of the extreme, and in this sense, sports achieves a lot of that with nonchalance. And the ideas that the sports world presents can then be absorbed and adjusted. In this sense, the exhibition is also a glimpse, drawing out these ideas that not only work in a certain context or environment, but also in other industries as part of everyday life.

Konstantin, how did you approach the exhibition design — what were you looking to convey?

- KG:

We wanted to have an architectural intervention that guides visitors around this rectangular exhibition area, telling our narrative from a clear starting point to a finishing point. That meant building a display system that could guide that movement. We opted to use super performance-oriented materials and colours that reflect the world of sports. But we weren’t making a kind of Disney World environment — instead, we were trying to follow the same logic as someone building an ice skating arena or the starting block of a ski race. That approach led to these walls made out of corrugated sheet metal that give the exhibition strong character and scenography. Exhibitions are not just educational, they are also entertainment. And we wanted people to feel immersed in this space, so that when they come out of it, it’s as if they are coming out of the cinema, away in another world.

- MS:

You don’t see literal references, but you feel that you are experiencing something that is very connected to the content. I’ve heard a lot of positive comments that the materials that Konstantin picked reminds visitors immediately of what you might see in the alps. And it’s also resonating with the installation that is outside the exhibition space, Refuge Tonneau by Charlotte Perriand and Pierre Jeanneret.

This exhibition coincides with the Milano Cortina Olympics. How does that relationship factor into the show?

- MS:

It was important to us that this be a show on during the Olympics, but not a show that is just celebrating ephemera from the Olympics. There’s no Olympic torch, or medals — there are medals and torches in other exhibition spaces in the Triennale mind you, but not in White Out.

We do explore how the Winter Olympics helped to make winter sports more popular around the world. We included a picture of an athlete competing in skeleton who is not someone from Scandinavia or Canada or Italy or Austria, but from Africa.

- KG:

Wthout the Olympics, sports like skeleton, luge, bobsledding and ski jumping would be gone by now. Who would ever learn to do those things, unless you came from a family that was already in the sport? But because of the Olympics, you see these competitions and they’re wonderful. I love them. Every four years, I zap into an Olympics curling event by accident and think, wow, these stones are beautiful objects. We have some in the exhibition that comes from a place in Scotland. And in fact, Achille Castiglione was inspired by curling stones to design a kettle.

I am especially pleased, with everyone in town, that the exhibition is free. It is attracting people, and they are spending some time here and developing a new appreciation for what they are watching at the Olympics — or maybe thinking “I must go skiing again myself.”

The Triennale’s Winter Sports Exhibition Shreds Some Pow

“White Out” explores the gear and infrastructure that make cold-weather athletics possible.