Mere steps from the ocean, and enveloped by mangroves, wetlands and gardens bursting with native flora, the newly opened Kymaia Hotel is at one with its surroundings just outside of Puerto Escondido in Oaxaca, Mexico. The latest hospitality venture by entrepreneur Ezequiel Ayarza Sforza is positioned as “an oasis where luxury and nature intertwine in a delicate balance” that celebrates sustainability, biodiversity and the cultural heritage of the region. To bring his holistic vision to life, Ayarza Sforza called on Mexico City–based architecture studio Productora, a firm known for context-appropriate and timeless designs that incorporate tradition and emotion along with a touch of playfulness and the unexpected.

“We wanted to create a strong connection between the

organic landscape and the hard architecture,” says Productora associate architect Natalia Badia of the resort, which comprises 22 private guest suites, three restaurants, a spa and a yoga studio, as well as walking trails and a pool. (Mexican design firm The Book of Wa was responsible for the interiors.) To establish that harmonious relationship with the land — one that complements the area’s natural beauty — the team employed traditional materials and building techniques that minimize impacts on the environment.

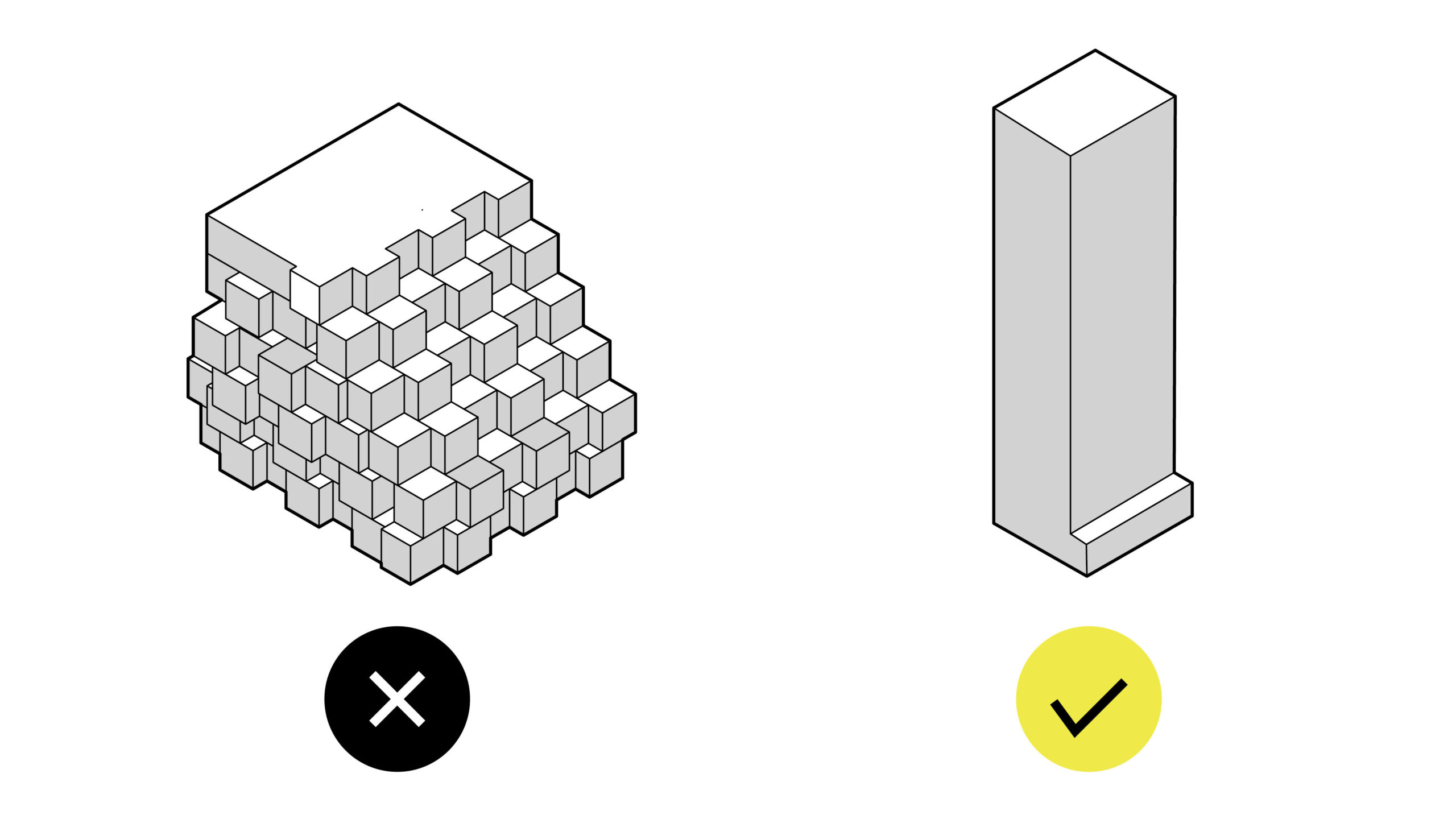

Inspired by pre-Hispanic pyramids, the individual guest suites were built from rammed earth blocks, approximately 500 of them per building. They were crafted by local artisans at a production site nearby, then carefully stacked by hand; thin horizontal poured-in-place concrete slabs between each row lend strength and stability. The stepped structures form a “containing element for the private spaces within the suites,” says Badia. “The material also acts as thermal walls that deflect heat and direct sun to keep the interiors cool.”

To ensure the interiors were as open as possible, an inverted structural beam system was used to support the flat roof without cluttering up the floor space. Projecting 1.5 metres out from the volumes, the clean-lined, pigmented-concrete roof slabs also provide a shading element that doesn’t distract from the organized silhouettes. Locally sourced Macuil wood lines the suites’ interiors — designed with a mix of Mexican and Japanese influences — and was used for the operable shutters that assist in cross-ventilation by controlling ocean breezes and minimizing sun glare during the day.

Complemented by Productora’s landscaping and bioclimatic methods — like solar energy and a wetlands system that treats wastewater before redistributing it into the ecosystem — the rammed earth structures that dot the grounds create a “synergy” with the landscape, one that is sensitive, supportive and nothing short of stunning.