The lighting in mega-chain economy hotels is rarely inspiring. Harsh fluorescents and unflattering overheads dominate; regardless of the time of day or night, the brightness is glaring. Tapped to imagine the interiors of a new Shanghai outpost of Ji Hotel — an H World International economy hotel brand with 2,000 locations across China — local firm Vermilion Zhou Design Group created a bespoke lighting scheme that not only vastly improves upon corporate chain standards but also elevates the guest experience.

Jointly led by founder and lighting design director Vera Chu, creative director Kuang Ming (Ray) Chou and interior design director Garvin Hung, Vermilion’s approach centred on an intelligent, manually controlled, scenario-based system that modulates lighting based on the time of day, flow of people and even weather changes to achieve illumination levels that feel natural and customized to each space’s unique function. The goal is for the lighting to “subtly guide [guests’] perception of the differences between spaces, as if they are gently enveloped in a natural environment,” Chu says. It begins in the lobby, where the lighting will change with the time of day, applying programmed settings for daytime, evening, late night and pre-dawn. In the dining area, intensity can adjust to complement the activity at hand, varying based on whether staff are preparing, guests are dining or the space is closed.

The system comprises a series of wirelessly con-nected devices that can be automated or directly controlled. In public areas, this is accomplished through button remotes and fixed points. In the private suites, voice control can be added to dictate lighting scenes or tune the brightness by degree, or presets can be selected on a control panel; for instance, guests can modify lighting levels using an intuitive console that features a range of percentages to represent a spectrum of corresponding lighting circuits. “Guests don’t need to choose a scenario; they just need to know whether they want it brighter or dimmer,” Chu says.

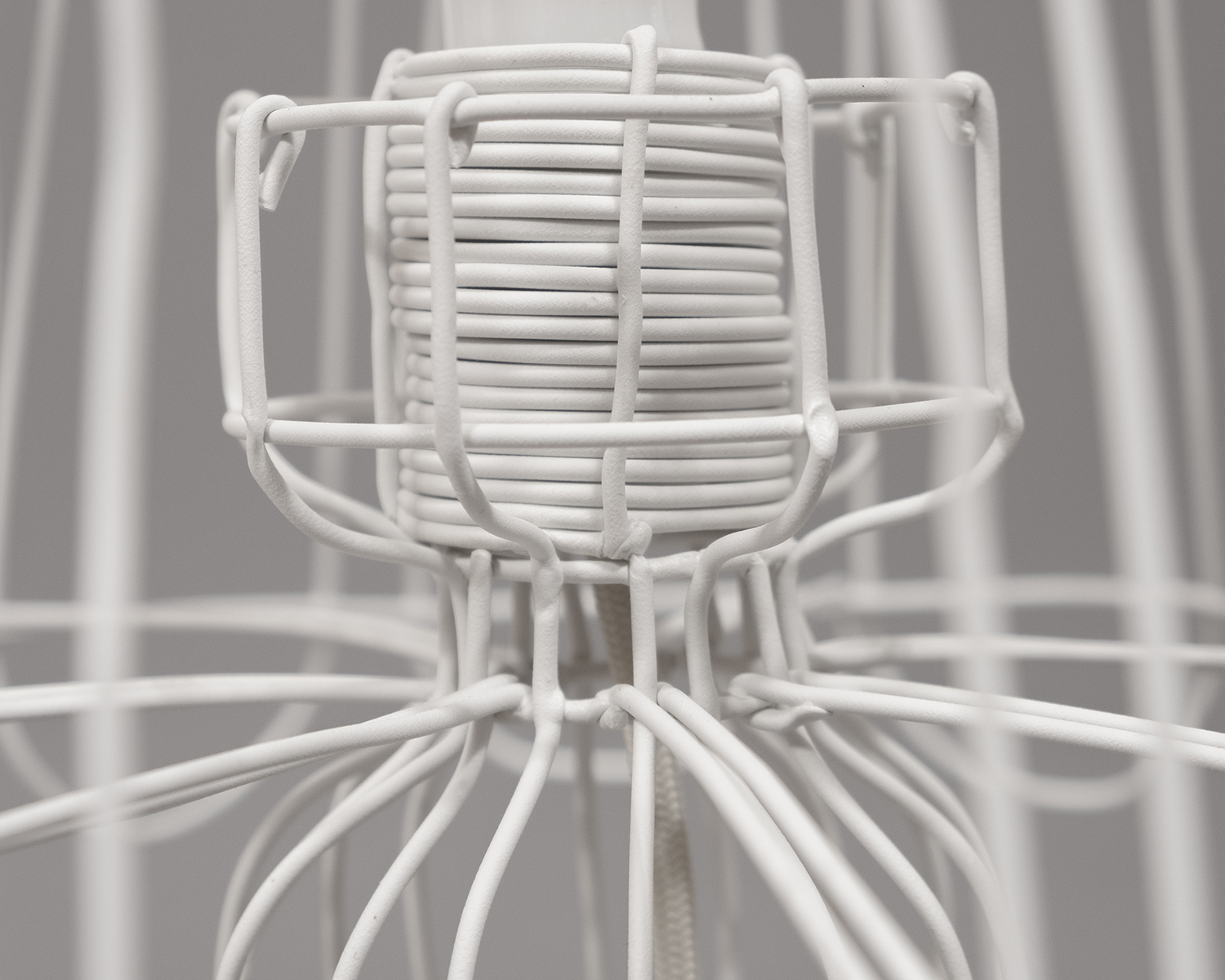

Key to the overall scheme is what Chu calls “the concept of ‘seeing the light but not the lamp.’ ” Vermilion eschewed most direct sources, opting instead for indirect, ambient ones, with some focus lighting in specific functional spaces. To that end, the guest suites contain no point lighting. Instead, some fixtures are uniquely incorporated in TV screens and mirrors to add dimensions of controlled brightness; high-efficiency LEDs, meanwhile, are seamlessly integrated into wall panels, ceilings and furniture. In the lobby-level tea bar, a backlit display case showcases products, while ambient illumination is integrated into the wall coves and ceiling to create a sense of depth and tranquility. In the lobby itself, low-contrast indirect lighting fosters a sense of openness. The thoughtful combination of form and function is what makes these chiaroscuro scenes so effective.

Vermilion delivered a solution that was environmentally friendly and replicable for future Ji expansions, one that it has continued to enhance and improve on. By adapting to time changes, the intelligent system can achieve energy savings (up to 30 per cent, according to the firm’s calculations) through optimized brightness levels; the integration of power supply and controllers reduces unnecessary electricity usage. Plus, the lighting fixtures were designed to be modular, allowing each element to be independently repaired or replaced, improving their overall lifespan. It’s a complex system design, but one that is simple to maintain and conscientious of the human encounter.