Philadelphians have long had a love–hate relationship with the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, a one-mile axis that runs from City Hall to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It may be leafy and lined with cultural landmarks, but its eight traffic lanes make it difficult to cross on foot, and it suffers from patches of undeveloped land — not to mention a dearth of places to stop for a drink. Around 2012, a few new parks, cafés and attractions opened, including the relocated and expanded Barnes Foundation, an elegant limestone rectangle from Tod Williams Billie Tsien set inside a formal landscape by OLIN. But the move for “more park, less way” has languished since then.

Now, on the other side of the boulevard, celebrated plantsman Piet Oudolf and architects Herzog & de Meuron have unveiled Calder Gardens, which will display an ever-changing assemblage of gossamer mobiles and monumental sculptures by Alexander “Sandy” Calder, who was born in Lawnton, Pennsylvania back in 1898 and raised in Philadelphia. The gallery lands on one of those formerly threadbare patches, and presents a seamless addition to an already remarkable trio of sculptures (known as the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost) found on the Parkway: Alexander Milner Calder’s 1894 statue of William Penn on top of City Hall, Swann Memorial Fountain (1924) by his son Alexander Stirling Calder at Logan Square and, at the furthest end of the Parkway, Sandy’s The Ghost (1964), suspended above the grand staircase of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

During a ribbon-cutting ceremony in mid-September, Alexander S.C. Rower, grandson of the artist and president of the New York–based Calder Foundation, which initiated the project, noted he presented no brief to its architects, simply asking, “Can you imagine spaces that can hold different works at various times of the year?” Jacques Herzog in turn praised the “blank canvas” of this broad mandate. “The beginning,” he said, “was just to understand the site.”

Some of the resulting design decisions were made in response to discoveries along the way. A 1910 map of the street grid and buildings that were demolished to create the Parkway informed the shape of one of the site’s sunken gardens, while downtown flooding in the aftermath of Hurricane Ida led to raising the building by two feet. With their low-slung, sunlit structure, the architects impel visitors to reach the galleries deeper underground by means of sneak peeks and surprising paths that play with space, stillness and materiality.

The ground level waits behind a trapezoidal wall sheathed in softly reflective stainless steel (paired with a metallic canopy over the porchlike entrance). This gives way as one enters to subterranean galleries clad in warm terrazzo stone, scored hemlock wood and blackened shotcrete that looks like lava — not exactly the concerns of colour, form and movement typically associated with Calder.

On the other hand, Rower turned to Oudolf specifically for his command of those elements. The Dutch master delivered with a variety of gardens — woodlands, meadows, sunken and prairie — filled with flowering perennials, shrubs and trees that will morph with the seasons, from spring bulbs to summer-into-fall blooms to the winter interest provided by seeds, pods and branches. Neither Calder’s work nor Herzog & de Meuron’s building drove Oudolf’s design. “For me, it’s always all about the plants,” he says. Maybe, but to find three creative geniuses working in concert in two tiny acres makes for one complete work of art.

Geometry 101

Neither a museum nor a sculpture garden (works are predominantly inside and presented with no context, labels or biographical sketches), Calder Gardens offers a host of magical set pieces

1

Eucalyptus (1940)

One of several works that gets its own niche, this mobile cascades from way up high and is lit in a Turrellian fashion that almost makes you doubt its solidity.

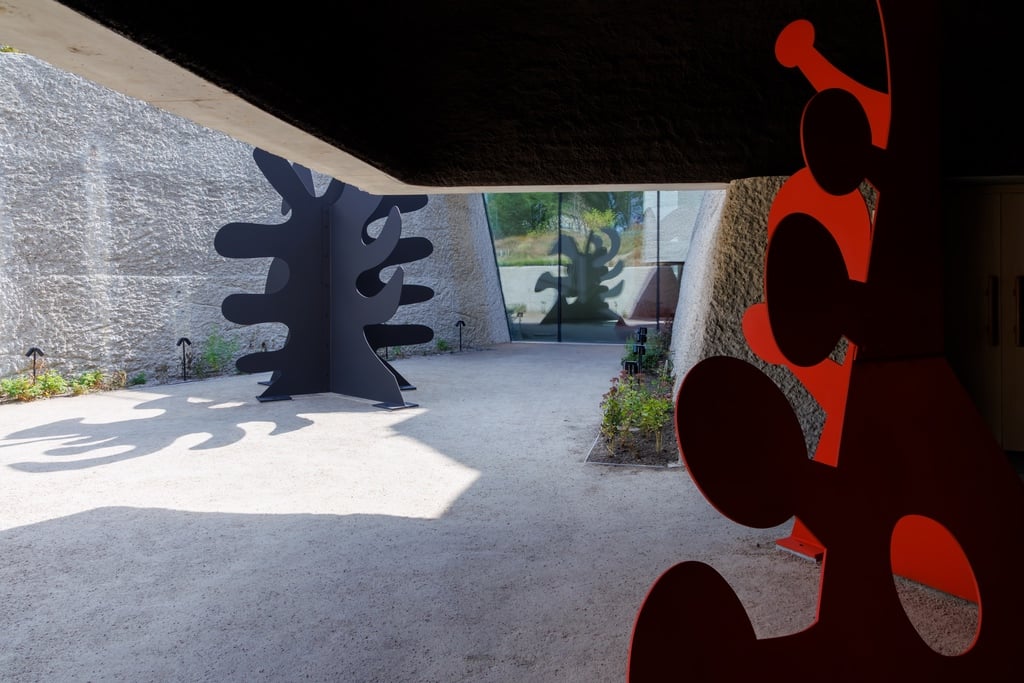

2

Knobs (1976) and Tripes (1974)

One red, one black, these sculptures pair off in the Vestige Garden, an outdoor space accessible from the inside. Both this area and the Sunken Garden will eventually be draped in vines, including wisteria, climbing hydrangea, honeysuckle and clematis.

Architecture, Landscaping and Alexander Calder’s Sculptures Enter a Shared Orbit

Herzog & de Meuron and Piet Oudolf sculpt a corner of Philadelphia into a monumental showcase for Alexander Calder’s geometric mobiles.