“We have built things with a lifespan of three days, 30 days and 300 years…” says Kevin Carmody, one half of London firm Carmody Groarke, referencing the practice’s diverse portfolio: the Skywalk Pavilion, which stood for three days during the London Architecture Festival in 2008; Studio East Dining, a temporary pavilion made from borrowed construction materials on a live Stratford site, which operated for three weeks in 2010; and the 7 July Memorial from 2009, designed to last 300 years, ensuring the victims of Britain’s worst post-war terrorist attacks are never forgotten.

“We like to think in factors of ten,” adds Andy Groarke, the other half of the partnership. Their playful camaraderie reflects the strong working relationship they have built over nearly two decades. Since establishing the practice in 2006, they have gone from strength to strength. Their Windermere Jetty Museum in the Lake District was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize in 2021, and their work has been celebrated in monographs by 2G, El Croquis and a+u.

Carmody grew up in Canberra, Australia, which he describes as a Garden City designed by Frank Lloyd Wright’s protégé Walter Burley Griffin and his wife, Marion Mahony. “The city was made for 3 million people, except that it only has a population of 300,000!” he laughs. Groarke, by contrast, is from Manchester. “Peter Saville — when he was running the branding campaign for the city — called it the world’s original modern city,” he recalls. “I think that is a brilliant description of a place that had to speed up through the industrial revolution and give identity to change. The city made a huge impression on me as a young person.” Appropriately, the second phase of their masterplan for the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester is now nearing completion.

One senses their conviction that social, cultural, physical and environmental change can be facilitated through the “discipline” of architecture. Before we sit down, Groarke speaks excitedly about his recent visit to the Walter Segal Housing Scheme in Lewisham — a radical self-build experiment from the 1970s, made possible by the visionary German émigré architect. “This whole community was built by people together and some of them are still alive and living there. It’s so impressive.”

Carmody Groarke is known for robust decarbonization strategies, which they say strengthen institutional resilience. Yet their success may lie more simply in bringing “different voices” to the table, “to get the best out of each opportunity.” Azure sat down with them in their Smithfield Market office after being invited to see their latest project at the John Soane-designed Dulwich Picture Gallery in London: ArtPlay Pavilion, a new building for children under eight, alongside the adaptive reuse and extension of the historic Gallery Cottage, Canteen.

You met working at David Chipperfield Architects. Did that studio culture influence how you work together?

- Andy Groake

We both worked on Antony Gormley’s studio when we were at DCA. In essence, we had two mentors: David (Chipperfield) and Antony (Gormley). From them, we learnt a way of designing buildings through an intense interest in physical things. We stay close to the physicality of things at all stages of the design process. If you walk around our studio, you’ll see lots of models and drawings on pin-up walls. We have design reviews daily. We bring lots of different voices into the studio to ask different questions. We are nomadic in where we take commissions, but London is the city we’ve chosen to base our studio and families. The city brings lots of commercial and creative forces.

- Kevin Carmody

Andy and I started doing competitions, designing and experimenting together from an early stage. What we’ve tried to do is extend a cultural practice of interrogating ideas. Working for Design Museum Gent in Belgium is a good example of how we work together. It’s a project steeped in collaborations. We’ve established a culture and environment of many voices, all bringing expertise from inside and outside the studio to get the best out of each opportunity.

- AG

There’s a wonderful artisanal studio called Local Works that, in the middle of Covid, helped us mix a brick out of construction waste materials and oyster and mussel shells. We worked with local partners in Ghent, our local architects Atama, and materials consultants BC Materials, to industrialize the process and get legislation for the bricks. We use municipal waste materials, which are effectively dirt cheap! 100,000 bricks have been made through their unique process. They take 100 days to dry out and sequester carbon for the next 100 years. Once the proof of concept is finished and delivered, we will make the recipe open source.

The questions you ask in your practice seem almost existential, not just the usual ones architects pose, such as what should we add or remove, but even why should we build? How do these questions drive your work?

- AG

We work a lot with this idea of continuity and change, reconciling tradition and innovation, asking questions like, how do we construct a new building in a dense context of landscape and historic architecture? How can we play with those memories and associations when imagining architectural identity? And thinking of innovation – what type of opportunity can we bring to the project? They are usually driven by an environmental consciousness.

- KC

If we go back to the beginning of the practice… we set up in 2006, then the recession hit in 2008. We began working with extremes of architecture. At one point we were designing the 7 July Memorial with a design life of a few hundred years, while at the same time we were designing provisional architecture with lifespans of three days or three weeks. It focused us early on to think about doing the most with the least – materially, physically and environmentally. We were also thinking, particularly with the temporary projects, about leaving a long-lasting impression for people visiting them. The responsibility of architecture for the memorial was about resisting amnesia, not letting people forget.

Your recent project at Dulwich Picture Gallery — particularly the ArtPlay Pavilion — plays with ideas of permanence and lightness. In what ways did you reinterpret John Soane’s architectural vocabulary, and how did that inform your design decisions?

- AG

Soane originally wanted a stone building but economized — so the gallery is built with London stock bricks and stone dressings. Soane lifts the heavy walls with subtle steps in the brickwork. We knew we didn’t want to use bricks but wanted to give our pavilion levity, so the timber wall steps out, inverting Soane’s load-bearing ziggurat building. We have made a timber frame ziggurat that gets bigger as it gets taller!

It’s very subtle, only small steps. The pavilion looks like it’s made from small pieces. We wanted it to feel handmade, more like a bandstand or garden pavilion with painted wood. We’ve kept the paint rough, with visible brushwork so the pinky Douglas fir comes through the grey-green paint. The metalwork of the canopies and the door recall the minty copper sulphate colour of the Soane Gallery’s front doors.

In designing the pavilion, how did you balance architectural expression with the goal of making the space feel open, inclusive, and socially engaging for visitors?

- AG

Soane’s building, built in 1817, is windowless, with daylight only from the roof. It was necessary to create lots of walls to hang paintings. It’s a wonderful piece of architecture as one of the first publicly visitable galleries, but it doesn’t necessarily engage new audiences. The idea was that as you come to one of the two entrances there, the form of the pavilion is aligned to face and greet you.

You’ve got this unfolding experience of a room in the landscape and with the big canopies that reach out in all directions, we felt it was important to extend the welcome of the building inside. Even though the pavilion’s constituency is for very young people, it is also a very important set piece of architecture and landscape.

That sense of welcome is really working. I went back to see the ArtPlay Pavilion again on a sunny day — only then I noticed that because you pivoted the pavilion at a 45-degree angle to Soane’s main gallery, when you walk through the main gate, the large circular windows on the walls line up perfectly, revealing the greenery beyond. The greenery was lit up brightly in the sunshine, creating a surreal mirage, as if the green was right inside the building. I saw people milling about near the Pavilion, some moving chairs under the canopy to keep out of the sun. Children were bouncing in Kim Wilkie’s new Lovington Sculpture Meadow next to it.

Kevin, is there any Australian architectural influence in the style of the building?

I think you are influenced by all your experiences. Growing up in Australia, I developed a climatological focus early on. My first three years of architectural education at RMIT were very technical, based on a Murcutt-esque idea of how you design architecture to shade well, to passively control the environment, and that somehow architecture is a direct response to inhabitation. But for us, it’s more about creating the connection to the landscape, the experience of it through architecture.

Andy and I talk a lot about “coats on experience;” the overhangs at ArtPlay Pavilion or Windermere Jetty Museum provide not only shelter, but also a definition of space in the landscape without full enclosure. It’s the sense of extending the welcome outwards.

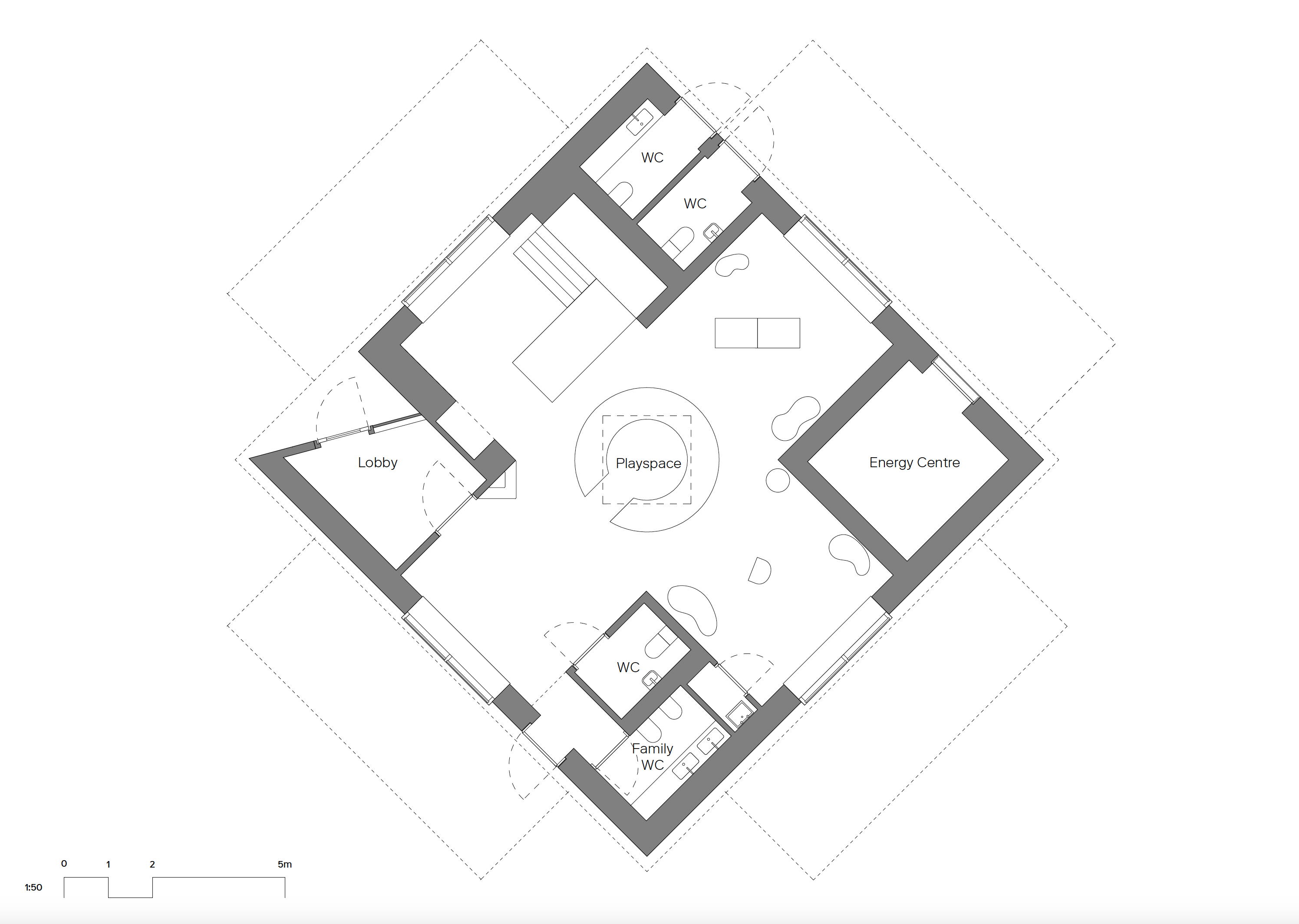

The pavilion has a cruciform plan, with one corner accommodating accessible toilets for the whole park and another containing a small energy centre that takes energy from a ground source heat loop, which can also heat Soane’s gallery. You ensured the pavilion’s carbon footprint is minimized by sourcing wood locally and designing a ceiling from short timber pieces. How important is it to help decarbonize institutions?

- KC

We just did a conference in Chicago on sustainability, and what was really apparent is that there is little impetus in the US for many institutional clients to decarbonize because gas and electricity are still relatively cheap. But we are increasingly called on as architects to coordinate the skills and expertise of a much wider field of specialists, engineers, artists and politicians – the very best minds in building technology – to optimize and build with as little carbon as possible.

- AG

Projects like the national repository of the British Library in Boston Spa and the conservation centre for Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Amiens come with full automation of storage and retrieval systems.

- KC

We have created a deoxygenated environment. Oxygen in air goes down to about 15 per cent, the same as base camp on Mount Everest. It’s like altitude training for sports people — a very specialist environment. Increasingly, architecture is about optimization and it’s one area where AI can help us, to think about how we can reduce materials and still achieve the most.

In your recent projects, you’ve been designing buildings for both people and machines, like archives and conservation centres. How do you see the architect’s role evolving in these increasingly automated environments? Is it perhaps more important than ever to reel back in human engagement?

- AG

Many building typologies are becoming less human. Buildings like the British Library’s archive require fewer people to store and retrieve the national collection. We’ve got to be careful with such typologies if we want to engage people through architecture. We’re interested in the physicality of materials — designing buildings that provoke an emotional reaction.

- KC

The role of the architect is not just about giving creative identity, drawing the look and feel of a building, but also about synthesizing many ideas to make more responsible and responsive environments.

- AG

Bibliothèque nationale de France takes its identity from making the enclosure of this high-tech super box sheathed in a veil of stainless-steel chainmail. It has a very unusual ethereal presence in the landscape. We are now dealing with client needs that weren’t even imagined a few decades ago. We need new architectural languages.

Is this the evolution of the chain mail enclosure you made for Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Hill House in Helensburgh?

- AG

Yes, but not just in material terms — also in the way we created a visitor centre at the heart of the box as part of the experience. It’s an important statement that these are public buildings.

- KC

The chainmail veil in Helensburgh creates a breathable layer where wind can whistle through, and the turbulence caused by that allows moisture to drop. More importantly, the chamber is 1 per cent solid, 99 per cent see-through. You can still see the house from outside. There was an epiphany moment with the client: if the house is visitable and visible, we can create a more human interaction with repair and conservation. If it were just a question of getting the right tin of paint, they would have done that 50 years ago. It’s not. This was a much more fundamental question of why we even care for these buildings.

- AG

These buildings, which take their cues from modern distribution warehouses, are unusual in scale. What we’ve done on the British Library masterplan is take that vernacular technology of the super shed but create small architectural steps in the surface. With shadows, you start to describe a more human scale that resonates with other buildings on the campus.

Power Hall at Manchester’s Science and Industry Museum is about to open to the public. What are you most excited about this project?

- AG

The Power Hall has the engines that would have powered all of that weaving and spinning that made Manchester’s fortune on display. Rather than have the new green heating system — which makes use of the aquifer deep below ground – behind a panel, we wanted to have that also on display and interpret it for visitors so people can see how steam is produced for the exhibits in real time. We’ve managed to reduce its carbon emissions by 515 tons a year, which is about the equivalent of 13 homes. This is about signposting and leading the way. We are also making the museum more permeable, with new public walkways connecting the site to the city to the north and south, to the east and west – yes, in the shape of a cruciform!

Yuki Sumner is a London-based writer, critic and curator. Yuki is currently working on a series of events exploring cultural interventions that aim to mitigate socio-economic disparities between rural and urban areas worldwide.

“Extending the Welcome Outwards”: A Conversation with Carmody Groarke

Led by Kevin Carmody and Andy Groarke, the London-based studio has quietly become one of the United Kingdom’s leading architectural practices.